- Piano

- Guitar

- Harmonica

- Other Questions

Piano Related Questions

I go by what the music tells me to do, and some songs want a slowly fading ending, fading on into the distance, sometimes feeling like it goes off into the distance, sometimes to give the impression of never ending.

And all the fades on my albums are done by playing softer and softer (except one song - the end of Minstrels on the DECEMBER album was an electronic studio fade). I grew up with my dad's 78 RPM records, where everything on the record is exactly how it was played, with no overdubs or electronic fades, etc. So when 45 RPM records and LPs came out later, I thought the band was just playing softer and softer, thinking everything on a record that I heard was actually played in real time.

Yes. The first four fully authorized sheet music books are now available from Hal Leonard. They features transcriptions of originals and interpretations of other composer's pieces. Other transcriptions that have not been approved by me all have varying degrees of inaccuracies, due to the unusual way I play (such as sustained notes vs. played ones, and what is played with the left hand vs. the right hand). All four books are currently available on Amazon, including EZ adaptations of some of my pieces.

The songs transcribed in the 1st songbook are:

1. Black Stallion

2. The Cradle

3. Graduation

4. Joy

5. Loreta and Desiree's Bouquet Part 1

6. Longing

7. Lullaby

8. New Hope Blues

9. Prelude / Carol of the Bells

10. Reflection

11. From THE SNOWMAN - Walking in the Air

12. From THE SNOWMAN - Building the Snowman

13. From THE SNOWMAN - The Snowman's Music Box Dance

14. Stevenson

15. Thanksgiving

16. Thumbelina

17. The Twisting of the Hayrope

18. Variations on Bamboo

19. Variations on the Kanon by Pachelbel

20. The Velveteen Rabbit

Guitarist Ed Wright, a good friend of mine, has transcribed 10 songs for a book titled GEORGE WINSTON FOR SOLO GUITAR, published by the Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation. It is now out of print.

In addition, the original sheet music for the song Graceful Ghost, by composer/pianist William Bolcom, (George rearranged and recorded a shorter version on his album, Forest) is available in a book William Bolcomb: Piano Works and is published by Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation.

Two good books of Vince Guaraldi's peanuts pieces are: THE VINCE GUARALDI COLLECTION - This has the most accurate transcription of Linus and Lucy available. It also has Cast Your Fate to the Wind, Christmas Time Is Here and Vince's wonderful arrangement of Greensleeves and five other songs. The other is The Peanuts Illustrated Song Book which has a nice introduction by Hank Bordowitz and 30 Peanuts songs including Skating, The Great Pumpkin Waltz, Christmas is Coming, and Christmas Time is Here.. Both are published by the Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation

The songs in the 2nd book, GEORGE WINSTON PIANO SOLOS are:

1. Fragrant Fields from SUMMER

2. Ike La Ladana from PLAINS

3. Lullaby 2 from REMEMBRANCE - A Memorial Benefit

4. Minstrels (Night Part 3) from DECEMBER

5. New Orleans Slow Dance from GULF COAST Vol 2

6. Peace from the album, DECEMBER

7. Remembrance from LINUS & LUCY The Music of Vince Guaraldi Vol. 1

8. Returning (in G minor) and The Cradle/(Returning in B flat minor) from FOREST

9. Sea from AUTUMN

10. Snow (Night Part 1) from DECEMBER

11. Theme for a Futuristic Movie from BALLADS & BLUES 1972

12. Troubadour from FOREST

13. Valse de Frontenac from MONTANA

Totally essential for the approach I have (I very rarely use written music). A great place to start is by learning chords: the first building block is the Major chords - then the minor chords, then the sevenths (the Major, minor, and dominant sevenths), then the augmented, diminished, and half-diminished chords, then ninths (major & minor), sixths (major & minor), then thirteenths and elevenths, and so on.

I encourage everyone to then study music theory, which is how these chords relate to each other the tendencies, and the rules, which you can then break. It is an excellent way to understand and memorize music. You can then analyze written scores (I always analyze recordings when learning a song, I usually like to hear many versions of it, and as many different versions by the same artists as possible as well sometimes I take the uneducated route first, just playing what I remember of a piece, and making variations, then educate myself later I find I often keep my variations).

Many Northern American musicians who play jazz, rhythm & blues, rock, and folk use music theory extensively. I recommend asking your music teachers to teach you music theory, if they don't already, and, again, the best place to start is with learning the chords.

Here is a chord chart and some information that I pass out when I give workshops.

I enjoy giving workshops when I can for any age group, time allowing and there is no charge. I do make materials available, the concert programs from the solo piano concert, the solo guitar concert and a workshop sheet of chords, intervals/ear training, modes & scales, solo guitar, solo harmonica, and more. I also go over how I play solo harmonica, solo guitar (in open G Major tuning D-G-D-G-B-D - from the lowest pitched string to the highest), and if a piano is available, the three solo piano styles I play melodic folk, stride piano, and New Orleans R&B.

I use the Marantz PMD-201 2-speed monaural Music Study Recorder. It has a speaker so you don't have to use headphones, pitch control to vary the speed and (most importantly for me) a half-speed switch which lowers the music one octave in the same key. It may not be exactly in pitch at half speed (it's often a half-step or a quarter-tone low), but you can use the pitch control to tune it to the piano. It also has a built-in microphone for taping, and a built-in speaker (it is a mono machine). In the past, they also made similar machines for CDs, and I haven't tried them, but I have heard good things about them. You may find on Ebay.

The nine-foot Steinway concert grand works best overall for what I do. It really depends on the individual instrument though.

About 80% - 90% of what I work on are R&B, slow dance songs, Soul, Rock, a bit of Latin, etc., for the solo piano dances I play. The other 10% - 20% are songs for the concerts: melodic pieces, stride piano, and Vince Guaraldi's Peanuts soundtrack pieces.

About 95 % of all the pieces I play are by other composers almost all North American. My temperament is much more that of an interpreter than as a composer. The composer who I have played the most songs of is Vince Guaraldi (46 songs). Very few of the pieces I have arranged by other composers were originally solo piano pieces – only 13 overall ever.

I compose 1 or 2 songs a year, and it happens occasionally, without any planning or intent to compose, as I am practicing, and it always happens at the piano, as opposed to in my head away from the instrument. Sometimes it happens when I am inspired by the Season, Montana, etc., and sometimes it just happens without any feeling at all. Most of the songs I compose, however, evaporate away in a day or a week. The ones that stay get used for a concert, or a recording, or a dance.

Most of my practicing is working on the musical languages of R&B piano - most specifically the great New Orleans pianists Professor Longhair (the founder of the New Orleans R&B piano scene in the late 1940s), James Booker (whose language is basically the way I think of playing in terms of), and Henry Butler, who is the pianist I am studying the most.

Also, on the guitar the languages I improvise in are Hawaiian Slack Key, Appalachian/American folk music, and popular standards. On harmonica, I play songs from three traditions: Appalachian, Celtic, and Cajun.

Some songs just get used for one function. I just see where each song goes, what it is to be used for. I have no personal mythologies or philosophies, or any connection to any movements, etc. - I am simply dealing with just these three elements: the music (the songs on the three instruments), the seasons & the places which give me the inspiration to play, and gratefully, the audience to play for.

I had a few piano lessons as a kid, but wasn't interested and quit. I was always an avid listener when growing up, especially to instrumental music, and especially to organists. Finally, in 1967, when I heard the Doors, I had to start playing organ. I learned chords and music theory, and studied recordings of organists, especially the great Jazz organist Jimmy Smith. Then in 1971, when I heard recordings of the great Stride pianist Thomas "Fats" Waller (1904-1943), I switched immediately to solo piano. I never played any music from the great European classical tradition, nor have any desire to. My approach is entirely North American, rather than European and I treat the piano as an Afro-American tuned drum.

"Stride" piano basically means that the left hand "strides" between a bass and a chord while the right hand plays the improvisation. It is an older jazz piano tradition, played most predominantly between the 1920s and the early 1940s. Stride piano came some out of the ragtime tradition of Scott Joplin and the other great ragtime composers from the early 1900s, but the tempos are much faster, there is much more improvisation, and more harmonic development. Some of the greatest stride pianists were Thomas "Fats" Waller (1904-1943), James P Johnson (1891 -1955), Willie "the Lion" Smith (1897-1973), and Donald Lambert, just to name a few. The great post-stride pianists Teddy Wilson (1911-1986), Art Tatum (1909-1956) and Earl Hines (1905-1983) could play fantastic stride piano as well. Three of the pianists who are the bridge between ragtime and stride are Eubie Blake (1883-1983), Luckey Roberts (1887-1968) and Jelly Roll Morton (1890-1941).

Some great later and contemporary stride pianists are also Dick Hyman, the late Ralph Sutton (1922-2001), the late Dick Wellstood, the late Joe Buskin, Mike Lipskin, Jim Turner, Tom McDermott, Brad Kay, Judy Carmichael, Marcus Roberts, Butch Thompson, and Barry Gordon (note -there are two pianists with the name Barry Gordon - the one referred to here is a different person than the one who has some recordings out).

Here are links to more info on Stride piano and Stride pianists.

Book on stride piano: Judy Carmichael - You Can Play Authentic Stride Piano - includes song book, easy 'how-to' drills, special tips and a CD.

I keep small black rubber mutes (wedges) inside the piano. If the out of tune note is one of the notes that has three strings in the upper half of the piano, then sometimes in between songs, I put the mute in between the left two of the three strings, leaving the very right string untouched (no matter which of the three strings of a note is out of tune, always do it this way, otherwise you'll have problems with the note not sounding when the soft pedal is used). The higher up on the piano the less this changes the sound of the note. If it is a lower string with just two strings or one string, there is nothing I can do, but I try to hit the note less hard or, if it fits with the song, play that note an octave above it or below it, but usually I just play that note softer (or not at all sometimes) and emphasize more of the other notes around it.

Three ways:

- One way is like getting artificial harmonics on the guitar - with the left hand reach way inside the piano past the hammers, around octaves 4 & 5, and towards the middle of the inside, and with the index finger lightly touch the left of the three strings (each note in that part of the piano has three strings). At the same time, pluck that string with the thumbnail. Unlike on the guitar where you have fret markings, this is pretty much intuition but does improve with practice. I am usually aiming for the harmonics that is an octave above the note of the string (like playing a natural harmonic on a string at the 12th fret on the guitar), but you can experiment with other harmonics, like the equivalent of playing a natural harmonic on the guitar on a string at the 5th fret (sounding 2 octaves above the note of the string), the 7th fret (sounding an octave plus a fifth interval above the note of the string, or the 9th fret (sounding 2 octaves plus a Major third interval above the note of the string).

- Again, hold the left hand way inside the piano past the hammers, around octaves 4 & 5, and slant the hand until the index finger and part of the hand is lightly touching the strings, slanted so the index finger is a bit nearer the keyboard and the rest of the hand is a bit farther away from the keyboard. While doing this, strike the keys normally (I hit them pretty hard). Like the technique in #1 above, it takes intuition and practice. Again, I am usually aiming for the harmonics that is an octave above the note of the string (like playing a harmonica on the 12th fret on the guitar), but you can experiment with other harmonics (like the equivalent of playing a natural harmonic on a string at the 5th, 7th, or the 9th fret on the guitar)

- This is a bit similar to technique #1 above. Around the low second octave, touch the string lightly in the space before the hammers and strike the key normally (I usually strike the key a little less hard then in # 2 above).

(for harmonics on the harmonica, see the question below "How do you get harmonicas on the harmonica?")

(this also includes information on the song An African in New York) One of four things:

- Muting the strings - usually on the closest part of the string(s) toward the keyboard, with the left hand and playing the keys normally with the right hand. The right hand playing is similar to playing guitar, as the thumb plays the lower notes and the fingers play the higher notes - (see Dubuque on the Plains album, Forbidden Forest on the Forest album; the end of the song Cast Your Fate to the Wind, on the album Linus & Lucy - The Music of Vince Guaraldi; on the song My Wild Love, from the album Night Divides the Day - The Music of the Doors and on the song Pine Hills, from the 20th Anniversary Edition of the album Winter Into Spring.

I also do this on the end of the live version of the song Woods, muting the very low notes, on the live version in the SUMMER SHOW, and also on the song An African in New York, that I play live sometimes in the SUMMER SHOW). It is a four part song and part of the first part was inspired by the work of the great South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim (AKA Dollar Brand), and all of the Africans who have immigrated to New York - and in fact, all New Yorkers. - Plucking a string - at the beginning and near the end of the live version of the song Woods, in the SUMMER SHOW – here a note is plucked with the left hand an octave lower than the same note played normally on the keyboard with the right hand to fatten it up, as if there is a bowed bass, I also do the same thing in the introduction of the song Cast Your Fate to the Wind, on the album Linus & Lucy - The Music of Vince Guaraldi. I pluck low bass notes also on the beginning on the song My Wild Love, from the album Night Divides the Day - The Music of the Doors. Also on the song Midnight, from the album December, I pluck the strings for the whole song.

The strings can also be scraped with the nail, although I have not done that on any songs yet. - Tapping the strings - see the first part of the song Tamarac Pines on the Forest album, I don't do this when I play this song live, as a medley with the song Colors, from the Autumn album, in the WINTER SHOW, as it is inaudible.

- Playing a harmonic chime - by lightly touching a string at a certain place with the left hand, and plucking it with the right hand, like it is done on the on the guitar (sometimes done near the end of the live version of the songWoods, from the Autumn album, in the SUMMER SHOW).

I use my thumb and middle finger, and you can substitute the index finger for a while if the middle finger gets tired. I also, inspired by Bluegrass mandolin players, sometimes let the little finger hit notes above the notes that the thumb and middle finger are playing, and it hits notes half the time that the thumb and middle finger hit notes. It does sometimes give the aural illusion that the little finger's notes are being played as rapidly as the ones with the thumb and middle finger.

One of the things I love about the piano is its sustain. I like this sustain better than the sustain of strings, organ, or synth, so that is one of the reasons I always play solo, to hear that sustain (the other reason is that is how I hear music in my head, is solo - what I am really, is a solo instrumental player that uses the piano, guitar, and harmonica. About 95 % of the songs I play are adaptation of songs by other composers, very few (nine) which were originally solo piano pieces by the original composers - what I do is the opposite of most arrangers, I go from big to small, adapting band and ensemble pieces to solo (most arrangers go from small to big, conceiving arrangements for the band or ensemble at the keyboard. So I sustain as much as I can, because I want a big sound. Also I spent my first few years of that I played on the organ, so I got used to having different sounds, having sustain, and a fat sound.

For Stride Piano, I have the exact opposite approach, here I often just briefly pedal the bass notes, to give them a fatter sound, like a string bass.

I also take off my shoes to minimize the sound of the foot pounding on the floor, and to have better control on the pedals.

I like the total acoustic sound, and I play better that way, and I dislike the sound with a mic for my ways of playing. I am influenced some by the sounds of electronic instruments, but I reflect those influences on acoustic instruments. Playing the piano wears my nails down, so I play the guitar with just the fingertips of the right hand, and I have to generally mic the guitar to be heard. I have more of a tolerance for a mic on the guitar. And as long as I am using a P.A. for the guitar, I use it for talking and the solo harmonica as well. However, the best situation for me is a very small hall, with no mic at all.

The solo piano dances I do, is where the piano is a one man band kind of thing which go 3 hours or more, of one long medley of R&B songs, slow dance songs, Soul, Rock, Vince Guaraldi Peanuts pieces, and a bit of Latin, Blues, and occasional waltzes (these are not Modern Dance/Ballet piano dances).

My concept of the piano, whatever style I am playing, is a band approach (a North American approach, rather than the European classical orchestral approach). Basically the left hand is the bass and rhythm, and the right hand is the lead singer and sometimes an additional rhythm, and the whole thing is the drummer.

Primary Direct Influences (extensive studying of their musical languages):

{Keep in mind that each musician is really their own category, and that categories only tell you what someone doesn't do, and that only narrows things down a bit, one has to hear each one to get a cognition}

- James Booker - New Orleans R&B pianist (1939-1983) - His musical languages are the main way I think in terms of playing the piano. I learned more from his album Junco Partner than any other album about how I want to play the piano. I have been studying him since 1982 when I first heard him.

- Henry Butler - New Orleans Jazz and R&B pianist (1948-2018) - I have been studying him since 1985 when I first heard him, and I am still just scratching the surface of what he did.

- Professor Longhair - New Orleans R&B pianist (1918-1980) - I have been studying him since 1979 when I first heard him, and I am just now starting to come to terms with what to do with his influence. He was my inspiration to start playing again after I had quit in 1977.

- Thomas "Fats" Waller - Harlem Stride pianist (1904-1943). I have been studying him since 1971 when I first heard him, and he was my inspiration for switching from organ to piano.

- Teddy Wilson - Stride and Swing pianist (1912-1986) -I have been studying him since 1973, when I first heard him.

Secondary Influences

- Dr. John (1941-2019) - New Orleans R&B pianist

- Jon Cleary - New Orleans R&B pianist

- Ray Charles - (1930-2004)

- Earl Hines (1905-1983) Stride and Swing pianist

- Vince Guaraldi - (1928 -1976) Jazz pianist/ composer

- Abdullah Ibrahim (aka Dollar Brand) - South Africian pianist

- Philip Aaberg - Montana pianist/ composer (the only melodic pianist I have ever studied)

- Oscar Peterson - (1925-2007) Jazz pianist

- Art Tatum - (1909-1956) Jazz and Stride pianist

- Donald Lambert - (1904-1962) Harlem stride pianist

Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd 1918-1980) was the founder of the New Orleans R&B piano scene in the late 1940s. Some of his influences were the great blues and Boogie Woogie pianists of the 1920s and the 1930s, especially Meade Lux Lewis (1905-1964), Pine Top Smith (1904-1929), and Jimmy Yancey (1898-1951), and also Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, and Little Brother Montgomery, as well as blues pianists in New Orleans, such as Archibald, Sullman Rock, Kid Stormy Weather, Robert Bertrand, and the great blues and jazz pianist Isidore "Tuts" Washington (1907-1984); as well as New Orleans music in general, and the Caribbean and Latin music traditions. He was the reason I began playing again in 1979, after I had quit in 1977, when I heard his album with his first recordings from 1949 and 1953, NEW ORLEANS PIANO (Atlantic 7225), and especially his beautiful track from 1949, Hey Now Baby.

Called Fess and beloved and inspirational to all who heard him, and the foundation of it all to me and many others, he had many inventions (as they were called by the late great New Orleans pianist and composer Allen Toussaint) (1938-2015) on the piano. Allen talks about the influence this this video. He always put his own deep, definitive, unique and innovative way of playing on every song he composed or arranged. His playing, and his whole approach speaks volumes. New Orleans R&B piano starts here.

Professor Longhair inspired and influenced many pianists, including the late Dr. John (Mac Rebennack), the late Henry Butler, the late Allen Toussaint, the late James Booker, the late Fats Domino, Jon Cleary, Huey "Piano" Smith, the late Art Neville, the late Ronnie Barron, Harry Connick, Jr.,Tom McDermott, Amasa Miller, Josh Paxton, Davell Crawford, David Torkanowsky, Joe Krown, Tom Worrell, the late Cynthia Chen, and many many others.

New Orleans has a wonderful and incredible R&B piano tradition, beginning with the late Professor Longhair's recordings in 1949, and continuing today. Some of the great New Orleans R&B pianists playing there today are Jon Cleary, Davell Crawford, Joe Krown, Josh Paxton, Tom McDermott, Amasa Miller, David Torkanowsky, Tom Worrell, and many others. For listing of live performances and information on New Orleans music in general, see OFFBEAT MAGAZINE.

He always put his own wonderful fun-loving, yet deep stamp and twists on every song he played, whether it was an original composition or a great and often very different interpretation of another composer's song (hear his version of Hank Snow's I'm Movin'On, on Fess'album LIVE ON THE QUEEN MARY, and compare it to the original Hank Snow version). I always have open ears to notice these wonderful things when they happen in every song, and I notice more things every time I hear his recordings. He was so wonderful at telling stories with his instrumental solos - just listen to his instrumental Willie Fugal's Blues from his album CRAWFISH FIESTA; and with his lyrics as well.

At least 16 of Fess' inventions are:

- Fess' "Rhumboogie" (or sometimes called "Rhumba-Boogie") syncopated left and right hand playing style - see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO and ROCK 'N'ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT and BIG EASY STRUT:THE ESSENTIAL PROFESSOR LONGHAIR; and the song Her Mind is Gone from the albums CRAWFISH FIESTA and BIG CHIEF and BALL THE WALL! LIVE AT TIPITINA'S 1978 and BYRD LIVES!

- Another aspect of his Rhumboogie (or Rhumba-Boogie) left hand, using the Latin clave beat, with notes played on beats one, "two and" and four - he used this on many songs, as this was his favorite left hand bass to play - “ for example, see the song Junco Partner on the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO; and the song Hey Little Girl from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO (interestingly enough, this same clave beat was the favorite solo guitar bass pattern of the late Hawaiian Slack Key guitarist Sonny Chillingworth [1930-1994], who was very revered and influential in Hawai'i, similar to how Fess was in New Orleans).

- Push beats, with notes played just before the beat in left hand notes - sometimes for one note, and sometimes throughout a whole phrase - especially see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO and ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the song Walk Your Blues Away from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO; and the song Tipitina from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO.

- Rapid right hand triplets and sixteenth notes in many pieces - see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO and ROCK & ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the song Her Mind is Gone from the albums CRAWFISH FIESTA and BIG CHIEF; and especially in the song Hey Little Girl from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO;

- Double note crossovers rolls in the right hand, playing two notes together, one of them with the thumb and then slurring notes down, crossing the fingers over the thumb - especially see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO, and ROCK 'N" ROLL GUMBO, and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT, and also especially the piano solo in the song Hey Little Girl from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO album.

- Double note crossovers - rolls in the right hand, playing a right hand roll going up, then crossing the index finger down over the thumb at the end of the roll - on the song Bald Head, on the CRAWFISH FIESTA album, and his first version of Bald Head, from 1949 reissued on three of his albums and all his 78's, also TIPITINA-COMPLETE 1949-1957 NEW ORLEANS RECORDINGS.

- And another type of Double note crossovers - rolls in the right hand, playing two notes together, one of them with the thumb and then slurring notes down, crossing the fingers over the thumb - especially see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO, and ROCK ‘N’ ROLL GUMBO, and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT, and also maybe in the piano solo in middle of the song Hey Little Girl from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO.

- Two hand rolls ending with rapid right hand broken octaves with the thumb and then the little finger in the right hand - see the introduction for the song Tipitina, and also in the last verse of that song on the album ROCK & ROLL GUMBO; and the song Willie Fugal's Blues on the CRAWFISH FIESTA album, and on this song he used ascending rapid broken octaves going up in the right hand preceding them with a rapid lower left hand note in the fourth chorus of that song. He also sometimes used descending rapid broken octaves in the right hand preceding them with a rapid lower left hand note. And he also used descending broken octaves with the right hand alternating the broken octaves between using the thumb and then then the little finger, and then using the little finger and then the thumb in the songs in #5 just above. A related technique is the right hand broken octaves at the end of the song Mess Around on the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT.

- The incredible two hand drum roll technique in his instrumental break on the song Every Day I Have the Blues on the album LIVE ON THE QUEEN MARY (One Way Records S21 56844), and also on the albums THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT and BYRD LIVES!; and on the song Gone So Long, near the end of the song, on the album BYRD LIVES!.

- His wonderful and distinctive piano phrases for the chord progression of the late Earl King's (1934-2003) song Big Chief. His first version of these phrases was on his 1964 recording of Big Chief, reissued on the compilation album with Professor Longhair and other artists titled COLLECTOR'S CHOICE-FEATURING PROFESSOR LONGHAIR (Rounder Records), and it was also reissued on the compilation album with various artists MARDI GRAS IN NEW ORLEANS (on Mardi Gras Records). He later varied some of these piano phrases for Big Chief, which can be heard on the albums THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT and CRAWFISH FIESTA. It is amazing how he came up with this one (and all the others). what Fess said in the newly issued long in-debth interview with the late filmmaker Stevenson Palfi in the documentary FESSUP (see https://palfifilms.com), about how he came up with things was that "I dream on it."

- His distinctive phrase for the IV chord (the C chord in the key of G, and the F chord in the key of C) - see the song Mean Ol' World from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO; and in his instrumental break in the song It's My Fault from the album CRAWFISH FIESTA; and in the song Gone So Long from the albums HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972 and MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE; and in the song Hey Now Baby from the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT.

- His use of repeating the tonic chord (the I chord) and/ or a tonic chord phrase in the right hand, over the IV chord (for example, in the key of C, playing the C Major chord over the F chord bass, creating the tonality of an F Major 7/9 chord) - see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO, and ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the songs How Long Has That Train Been Gone and Stag-O-Lee, from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO - these latter two songs are in the key of F, so here for the IV chord, he played the F Major chord over the B Flat chord bass, creating the tonality of a B Flat Major 7/9 chord. Fess also sometimes played a roll with the tonic Major chord throughout the whole chorus - see the song Doin' It on the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and the song Gone So Long on the album HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972 and MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE.

- His temporary altering of the rhythm within a song - see the song Mean Ol' World from the album ROCK & ROLL GUMBO; and the song Everyday I Have the Blues from the album THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the song Gone So Long from the albums HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972 and MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE.

- His playing of the root note of the chord on the beat "one-and" hesitating the bass note a bit, instead of playing it on beat one, in the second intro instrumental piano verse in the song Hey Now Baby, from the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT, and in the instrumental piano solo in the song How Long Has That Train Been Gone from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO.

- His use of broken octaves going up the notes of the tonic chord (the I chord), just before going to the IV chord. He did this in many songs including in the song from the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT, and the song Doin' It from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO , and with variations on Doin' It on the album MEET ME AT TIPITINA'S (aka MEET YA AT TIPITINA'S) ; and the song Her Mind Is Gone from the album CRAWFISH FIESTA; and notable variations of this, with push beats in the left hand before the right hand octaves, are in the introduction and in the middle instrumental solo on his 1950 recording of Byrd's Blues, which appears on two albums: THE MERCURY NEW ORLEANS SESSIONS 1940 & 1953 (a double compilation album with Professor Longhair and various other artists), and his album 1949; he also played different variations on these with both hands, with the left hand octave struck before the right hand octaves, especially before the change from the I chord to the IV chord, and also sometimes at the end of a verse, just before the beginning of the next verse.

- Another wonderful characteristic of Fess's playing is what I call his "Returning". By this I mean a very strong and definitive return to the bass note of the tonic chord in the middle of the verse or the beginning of the verse. Examples of this are his 1949 version of Hey Now Baby on his album NEW ORLEANS PIANO; also on his 1974 version of Hey Now Baby, and also Doin' It, Junco Partner, and Mean Old World, all also on his album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO.

Fess had many other wonderful short statements within songs, such as:

(1). his use of the Lydian Mode, using the raised 4th note of the scale (in a way different from using it in the Blues scale), in the second chorus of instrumental song Longhair's Blues-Rhumba, in one of the verses, from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO;

(2). his playing the notes of the normal left hand broken octaves Boogie Woogie bass line in the right hand, in the second chorus of the sax solo in the song Ball The Wall, from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO;

(3). and his playing of right hand octaves proceeded by a three note roll with the three notes chromatically before the highest note of the octave played very rapidly just before striking low lower and the upper notes of the octave.

(4). He was also one of the first pianists to play the popular rapid soulful blues lick that basically goes from the 5th note of the scale, then rapidly down to the 3rd, the tonic note, and the 5th note below that (often preceded by the minor 3rd note played together with the 5th note above it, as grace notes to the Major 3rd note played together with the 5th note , then going rapidly to the notes going down mentioned just before). Dr. John called it the "special lick", and has been used prominently by New Orleans pianists such as James Booker, Henry Butler, Dr John, Allen Toussaint, as well as by pianists Ray Charles and Oscar Peterson, and earlier by Memphis Slim. Every pianist that uses this lick has their own personal way of playing it.

(5). Fess used the keys that he favored on the piano, the keys of C, E flat, F, G, A flat and B flat, in a similar way that solo acoustic guitarists play in the natural Major keys of C, D, E, G and A, and each of those keys have their strong tendencies. He favored the keys of C, F and G for his up tempo and slow blues type pieces, and he used the keys of E flat (Big Chief and Bald Head) and B flat and A flat for occasional other types of songs.

- NEW ORLEANS PIANO (Atlantic 7225) - Great 1949 and 1953 tracks - New Orleans R&B piano starts here.

- ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO (Dancing Cat 3006) - Great 1974 tracks with the late Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown on guitar. For extended notes click here.

- THE LONDON CONCERT (JSP Records 202) - English import -1978 concert with just piano and conga.

- CRAWFISH FIESTA (Alligator 4718) - Fess' last album from 1980.

- HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE (THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972) (Rounder Records 2057) - 1971 & 1972 sessions in Baton Rouge and Memphis.

- MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE (Rhino Records) - more tracks from the 1971 & 1972 sessions in Baton Rouge and Memphis, with horns added later.

- LIVE ON THE QUEEN MARY (One Way Records) - live performance from 1975 - especially note the great version of Everyday I Have the Blues with Fess' incredible instrumental piano break.

- MARDI GRAS IN NEW ORLEANS (Nighthawk Records) - tracks from 1950 - 1957, including his beautiful composition from 1957 Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand.

- Fess' Mercury Records tracks from 1949 or 1950, (Classics Records [French import]) - and the Atlantic tracks from 1949 and 1953 (the Atlantic also appear on the NEW ORLEANS PIANO recording on Atlantic Records).

- THE NEW ORLEANS SESSIONS 1950 (Bear Family Records) an out of print LP that has Fess' 1950 Mercury Records tracks from the recording listed just above, plus four alternate takes (as well as tracks by other artists).

- COLLECTOR'S CHOICE-FEATURING PROFESSOR LONGHAIR (Rounder Records) this anthology recording with various artists features 10 tracks by Fess from 1958-1964, including his 1959 hit version of Go To The Mardi Gras, and his 1964 hit versions of Big Chief-Parts 1&2, as well as his first recording of his fast tempo arrangement of his classic composition Hey Now Baby, with the title Cuttin' Out, and seven other R&B singles from this time period

- FESS - THE PROFESSOR LONGHAIR ANTHOLOGY (Rhino Records) this double CD has Fess' 1959 hit version of Mardi Gras in New Orleans, and his 1964 hit version of Big Chief-Part 2, his great 1957 track Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand, and many other studio and live tracks from other years, and extensive liner notes.

- The 1978 live shows recorded at Tipitina's, many of these tracks have been issued on three different recordings:

- THE LAST MARDI GRAS (Atlantic Records) out of print double LP.

- RUM AND COKE (Tomato Records)

- BIG CHIEF (Rhino Records)

- BALL THE WALL! - LIVE AT TIPITINA'S 1978 (Night Train Records) a different live show from Tipitina's in New Orleans

- BYRD LIVES! (Night Train Records) double CD of more live 1978 tracks from Tipitina's in New Orleans - has Fess' only recording of the Blues standard After Hours, and has three rare solo tracks

Documentaries on Professor Longhair:

1. FESS UP:

Two-disc video and print package includes:

(1). the 1980 full feature-length interview with Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd) , Fess Up, filmed two days before his death;

(2). the restored 1982 groundbreaking film by Stephen J. Palfi, Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together, featuring Professor Longhair, Tuts Washington, and Allen Toussaint;

(3). excerpts from the 1987 documentary Southern Independents: Stevenson J. Palfi, on the work and films of the director, including intimate insight from Palfi into the making of Piano Players;

4). a 38-page hardback book with essays from Bruce Raeburn, Johnny Harper, and Michael Oliver-Goodwin, plus many never-published photos. The package comes from a team of filmmakers, writers, designers, and producers who knew and worked with Palfi. https://palfifilms.com/

2. Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together - Stevenson Palfi's 1982 documentary about New Orleans pianists Professor Longhair, Allen Toussaint, and Isidore "Tuts" Washington. (Now restored and remastered by Blaine Dunlap and the Palfi Family)

3. PROFESSOR LONGHAIR: Rugged and FUnky - upcoming documentary by Joshua JG Bagnall.

Book on Professor Longhair:

- PROFESSOR LONGHAIR - A SCRAPBOOK by Per Oldaeus. This book documents Fess' huge inspiration and influence.

James Booker (1939-1983) was the late/great New Orleans R&B pianist, who has been my overall biggest influence of how I think in terms of playing the piano. He was the first one to take R&B, soul music, New Orleans music, the blues and more and make a whole solo piano style out of those traditions. I learned more from his album JUNCO PARTNER than any other album ever. Some of his influences were Professor Longhair (1918-1980), Ray Charles (1930-2004), Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Art Tatum (1909-1956), Erroll Garner (1921-1977), Meade Lux Lewis (1905-1964), Albert Ammons (1907- 1949 ), Pete Johnson (1904-1964), Jelly Roll Morton, and many others.

biggest influence of how I think in terms of playing the piano. He was the first one to take R&B, soul music, New Orleans music, the blues and more and make a whole solo piano style out of those traditions. I learned more from his album JUNCO PARTNER than any other album ever. Some of his influences were Professor Longhair (1918-1980), Ray Charles (1930-2004), Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Art Tatum (1909-1956), Erroll Garner (1921-1977), Meade Lux Lewis (1905-1964), Albert Ammons (1907- 1949 ), Pete Johnson (1904-1964), Jelly Roll Morton, and many others.

He was musically fluent in all 12 major and minor keys. He was an outstanding organist as well, and his piano playing reflects that especially in his left-hand bass lines and his use of right hand, full-sounding chords and voicing. His unique, innovative, and deeply soulful arrangements of the songs he arranged often became the definitive and standard way of playing that song. His playing covered at least seven separate styles, and he had many inversions on the piano (the notes and the songs referred to here are from his JUNCO PARTNER album [Rykodisc 1359], which is the album I have learned more from than any other):

- An R&B band style, with single note bass line and a partial chord in the left hand played within a hand span of an octave or a 10th interval. (On this album you can hear this style on Good Night Irene, Pixie, Make a Better World, Junco Partner, Blues Minuet and Pop's Dilemma)

- A medium temp. hard winging stride style (stride piano meaning the left hand plays a bass on the on beat and then "strides" or jumps up to a chord on the off beat) with the root note and 5th below that played simultaneously just before the beat and the lower root note played on the beat. He played both standards and R&B pieces in this style (Sunny Side of the Street on this album).

- A slow and medium slow stride style with 10th in the left hand, preceded often by a fast chromatic roll, and the right playing bluesy fills and occasionally jazz lines (Until the Real Thing Comes Along/Baby Won't You Please Come Home, I'll Be Seeing You on this album).

- A rock stride style (Put Out the Light on this album).

- A romantic, classically-influenced style (Black Minute Waltz, I'll Be Seeing You on this album.)

- An organ-influenced style (not represented on this recording) with the octave bass line sparse and the right hand consistently going, often with choppy rhythms. James played a different version of Junco Partner than the one on this album in this style, as well as the song Papa Was a Rascal.

- A speeded-up version of his R&B band style (not represented on this recording), again with the bass line and partial chord in the left hand within a hand span. He sometimes used this style to play ragtime-type pieces and older pop songs such asBaby Face and Sweet Georgia Brown.

Some of my favorite albums of his are:

- JUNCO PARTNER (Rykodisc 1359)

- NEW ORLEANS PIANO WIZARD: LIVE (Rounder 2027)

- SPIDERS ON THE KEYS (Rounder C2119)

- RESURRECTION OF THE BAYOU MAHARAJAH (Rounder C2218)

- KING OF THE NEW ORLEANS KEYBOARD (Junco Partner JP1, JSP Productions) - English import

- PIANO PRINCE OF NEW ORLEANS

- BLUES AND RAGTIME (Aves INT 146.530 - out of print - German import)

Filmmaker Lily Keber has made a wonderful documentary of James, BAYOU MAHARAJAH.

Henry Butler is the late great New Orleans R&B/jazz pianist, who has been the main pianist I have been studying since 1985, and I am still just scratching the surface of what he has done. He is the only pianist I know of that plays the deep blues and R&B and mainstream jazz, two extremely different mind-sets and technical approaches. In my opinion, he has taken the R&B piano to its farthest heights, and he was a phenomenon to experience live. Each performance was deep to the core, and they are all very different from each other as he was an absolute master of improvisation. They are impossible to describe. His musical languages were very complex yet he always took one on the journey with him. I realized the first moment I heard him, that I would be studying his playing forever.

Some of his influences have been Professor Longhair (1918-1980), James Booker (1939-1983), Ray Charles (1930 -2004), McCoy Tyner, Art Tatum (1909-1956), George Duke and many more.

One of his greatest and most amazing inventions, one of many, is a percussive style that I call two hand conga playing where he plays very powerful syncopated rhythmic figures up and down the keyboard with both hands and/or with two hands answering each other in phrases. A great example of this is Henry's Boogie on his recording HOMELAND. Another major invention of his is the funk stride bass, with the feel of a whole funk band with the solo piano.

Some of his styles are rhythm & blues/funk, deep slow blues, mainstream jazz, impressionistic/classical influences, and stride piano.

His website is www.henrybutler.com.

Some of my favorite albums of his are:

- HOMELAND (BSR 0802 - 2)

- BLUES AFTER SUNSET (Blacktop 1144)

- BLUES & MORE VOL. I (Windham Hill Jazz 10138)

- ORLEANS INSPIRATION (Windham Hill Jazz 10122)

The great New Orleans R&B pianists are the ones who have inspired me to play the piano the most - especially Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd), James Booker, and Henry Butler, as well as Dr. John, Allen Toussaint, and Jon Cleary;

- and also New Orleans pianists Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton, Tony Jackson, Alfred Wilson, Albert Carroll, Sammy Davis, Game Kid, Buddy Carter, Josky Adams, Luis Russell, Frank Richards, Buddy Bertrand, Mamie Desdoume, Kid Rock (the early 1900s pianist), Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Clarence Williams, Frank Amacker, Sweet Emma Barrett, Jeanette Salvant Kimball, Billie Pierce, Dolly Douroux Adams, Lizzie Miles (Elizabeth Landeraux), Blue Lu Barker, Eurreal "Little Brother" Montgomery, Roosevelt Sykes, Isidore "Tuts" Washington, Richard M. Jones, Joe Robichaux, Burnell Santiago, Sadie Goodson, Olivia Charlot, Olivia "Lady Charlotte" Cook, Walter "Fats" Pichon, Alton Purnell, Manuel Manetta, Lester Santiago, Octave Crosby, Armand Hug, Don Ewell, Morten Gunnar Larsen, Butch Thompson, Sam Henry, Dave "Fatman" Williams, Al Broussard, Pleasant "Cousin Joe" Joseph, Henry Gray, Kid Stormy Weather, Sullivan Rock, Robert Bertrand, Champion Jack Dupree, Paul Gayten, Walter Decou, Alex "Duke" Burrell, Eddie Bo (Bocage), Archibald (Leon T. Gross), James "Sugar Boy" Crawford, Herbert "Woo Woo" Moore, Ellis Marsalis, Ronnie Kole, Frank Strazzeri, James Drew, Roger Dickerson, Huey Smith, Art Neville, Salvador Doucette, Fats Domino, Edward Frank, Esquerita (Eskew Reeder), Tommy Ridgley, Willie Tee (Turbinton), John Berthelot, Big Chief Jolly (George Landry), Al Johnson, Ronnie Barron, Carol Fran, Tom McDermott, Amasa Miller, David Thomas Roberts, Dave Paquette, David Torkanowsky, Phil Parnell, Harry Connick, Jr., Joshua Q. Paxton, Joe Krown, Frank Chase (Professor Bigstuff), Bob Andrews, Davell Crawford, Ivan Neville, John Magnie, Rickie Monie Tom Worrell, Marcia Ball, Mitch Woods, Philip Melancon, Luther G. Williams, Tom Roberts, Joel Simpson, David Egan, Bob Greene, Lars Edegran, Bob Discon, Roy Zimmerman, Stanley Mendelson, Larry Seiberth, Eddie Volker, Willie Metcalf, Doug Bickel, Frederick Sanders, Richard Knox, Phamous Lambert, John Brunious, Ed Perkins, Walter Lewis, Peter Martin, Peter Cho, Darrell Lavigne, Emile Vinette, Jonathan Batiste, Victor "Red" Atkins, Frederick James McCray, Jesse McBride, Ronald Markham, Matt Lemmler, Richard Johnson, John Royen, John Autin, Michael Pellera, Jim Markway, Paul Longstreth, Tom Hook, Mike Dennis (aka Mike Bunis), John "Papa" Gros, Ronald Markham, Marc Adams, David Reis, Chuck Chaplin, Noah Levi, Adam Matasar, Sanford Hinderlie, Lawrence Cotton, "Piano Bob" Wilder, Nelson Lunding, David Boeddinghaus, John Sheridan, Lawrence Sieberth, Steve Conn, Thomas Gerdiken, Keiko Komaki, Artie Seeling, Stanley Mendelson, Jim Hession, John Mahoney, Craig Brenner, David Morgan, David Ellington, Glenn Patscha, Austin Johnson, Warner Williams, Ralph Gipson, Michael Bagent, Kim Phillips, Marvell Thomas, Craig Wroten, Sammy Berfect, C. R. Gruver, Bill Malchow, Judith Owen, Mari Watanabe, Paul David Longstreth, Cynthia Chen, Conus Pappas, Jr., Wil Sargisson, Mike Wadsworth, Mike Esnault, Lee Pons, Richard Scott (Scott Obenschein), Jimmy Maxwell, Bart Ramsey, Bobby Lounge, Zaza Marjanishvili, Big Mama Sunshine, Brett Richardson, Brian Coogan, Eduardo Tozzatto, Jonathan Lefkowski, Steve Pistorius, Marco Benevento, Kenny Bill Stinson, Davis Rogan, Nicholas Sanders, Wilson Savoy, and so many other New Orleans musicians.

Thomas "Fats" Waller (1904-1943) was, in my opinion, the greatest of the stride pianists. He had an amazing combination of power and yet effortlessness and finesse in his playing. He grew up in Harlem and his main influence was the great stride pianist James P Johnson (1891-1955). Some of his greatest playing is on the instrumental breaks of his tracks with his band Fats Waller & His Rhythm, especially between 1934-1936. He also composed many songs, including Ain't Misbehavin' and Honeysuckle Rose in 1929, his signature instrumental piece Handful of Keys, and many others. He was my inspiration, upon hearing his recordings in 1971, to instantly switch from organ to piano. Fats Waller's websites is - www.fatswaller.org.

Some of my favorite recordings of his are:

- FATS WALLER PIANO SOLOS - TURN ON THE HEAT 1929-1941 (RCA/Bluebird 2482)

- THE JOINT IS JUMPING (RCA/Bluebird 6288)

- And especially any tracks with his band "Fats Waller & His Rhythm," between 1934 and 1936.

- And see the book Fats Waller, an excellent autobiograhy by his son Maurice Waller.

Teddy Wilson (1912 -1986), was the great swing and stride pianist who was best known for playing with the Benny Goodman (1909-1986) Trio & Quartet from 1935-1939. This incredible group also featured the late Lionel Hampton (1908-2002) on vibes and the late Gene Krupa(1909-1973) on drums. Teddy also backed up singer Billie Holiday on some of her first recordings in the 1930s. He also made his first amazing solo recordings in 1934, 1935, and 1937, and he made many recordings up to his passing in 1986.

Teddy Wilson was not only the most influential jazz pianist of the late 1930's to the early 1940's, he was also the first one to break the color line, playing the first integrated public concert, with the Benny Goodman Trio in Chicago on Sunday, April 12, 1936. One of his many inventions was to play moving bass lines with his left hand in tenth intervals. Another was his flowing right hand lines, played at the same time. He told me that in 1928, he had heard Fats Waller, and that influenced him to play jazz piano rather than classical. I was thrilled to be able to tell him that in 1971 I had heard Fats Waller’s recordings, and that made me switch from organ to piano. His other main influences where the great pianists Art Tatum (1909-1956), and Earl Hines (1905-1983).

Some of my favorite recordings of his are:

Solo piano: Especially his piano solos in 1934, 1935 and 1937. These are available on the following recordings:

- Solo piano: THE COMPLETE TEDDY WILSON - PIANO SOLOS 1934-1941 (2 CD set) (CBS 4676902) - French import - Out of Print. There are other recordings that feature his piano solos from 1934, 1935, 1937.

- SUNNY MORNING (Musicraft/Discography 2008) - piano solos recorded in 1946

- TEDDY WILSON - PIANO SOLOS (Charley Records CD-AFS 1016) - British Import - This recording also has all the 1934, 1935 and 1937 piano solos.

Some of these piano solos are also available on the following five recordings:

- TEDDY WILSON AND HIS ORCHESTRA - 1934-1935 (Classics Records - Classics 508)

- TEDDY WILSON - VOLUME 1 - 1934-1941 THE ALTERNATIVE TAKES (Neatwork Records - Neatwork R2021)

- TEDDY WILSON AND HIS ORCHESTRA - 1935-1936 (Classics Records - Classics 511)

- TEDDY WILSON AND HIS ORCHESTRA - 1937-1938 (Classics Records - Classics 548)

- TEDDY WILSON AND HIS ORCHESTRA - 1939-1941 (Classics Records - Classics 620)

With the Benny Goodman Trio & Quartet (with Benny Goodman on clarinet , Teddy Wilson on piano, Gene Cooper on drums, and as quartet Lionel Hampton on vibraphone - Teddy's incredible left hand playing 10th intervals provided the bass for the trio & quartet):

- BENNY GOODMAN -THE COMPLETE RCA VICTOR SMALL GROUP RECORDINGS (09026-68764-2) - 3 CD Set

- LIVE AT CARNEGIE HALL - 2 CD set

Pianist Earl Hines (1903-1983) was one of the greatest early jazz pianists, and is sometimes referred to as the first modern jazz pianist. On May 9, 1927 Earl Hines and trumpeter Louis Armstrong made their first recordings together, defining the beginnings of modern jazz, and on December 8, 1928 Earl recorded his definitive eight piano solos composition that further defined modern jazz piano: A Monday Date, Chicago High Life,Stowaway, Chimes in Blues, Panther Rag, Just Too Soon, Blues in Thirds, and Off Time Blues. He was also well known for his performances and radio broadcasts with his big band in Chicago in the 1930s, and for his composition Rosetta.

Here are his earliest recordings:

- THE EARL HINES COLLECTION 1928-1940 - All of his piano solos from these years (except Melancholy Baby)

- THE EARLY YEARS: 1923-1942

Donald Lambert (1904-1962) was a great stride pianist who played in New Jersey clubs and sometimes in Harlem. He made four great recordings in 1941: Anitra's Dance, Sextette, Pilgrim's Chorus, and Elegie, and also some live recordings between 1959 and 1961, that have been reissued on two CDs: .

I like that situation, as each piano is very different and each one brings something different out of the songs. I also like playing in different places, as each town also affects and brings something new and different to the music.

I play three styles:

- R&B piano - Inspired by the great New Orleans R&B pianists from the late 1940s onward, especially:the late Henry Butler, the late James Booker, the late Professor Longhair (the founder of the New Orleans R&B piano scene, much like the late Gabby Pahinui is the father of the modern Hawaiian Slack Key guitar era), as well as the late Dr. John and Jon Cleary. The vast majority of songs, about 90% I play are in this style, and they are mainly played at the solo piano dances I do, but I use some songs played this way at concerts and recordings (especially on the recordings Linus & Lucy - The Music of Vince Guaraldi, and Night Divides the Day - The Music of the Doors.

- Stride Piano - (see # 5 above) I play just a few songs in this style now. It was the main thing I worked on in the early 1970s, but over the years my main approach became R&B piano.

- Folk Piano - this is a combination listening as a kid to the instrumental R&B and rock, and American folk music. This is the melodic style I came up with in 1971, when I had switched from organ to piano, and I was mainly working on stride piano, and I wanted something that was complimentary to that, melodic and simpler, and using the sustain sound of the piano that I love. The majority of songs on my recordings are in this style (and it is rural in nature, rather than urban), and I like to stay within the theme of the album. About 10% of all the songs I play on piano are in this style.

Yes. I came up with the melodic style that I play in 1971, and I have always called it "Folk Piano", (or more accurately "Rural Folk Piano), since it is melodic and not complicated in its approach, like folk guitar picking and folk songs, and has a rural sensibility. When the Autumn album came out in 1980, I was first sometimes mislabeled as classical, but I have never played any European classical music, and I don't have any classical influence (I treat "Variations on the Kanon by Pachelbel" from the December album in a folk way, basically improvising on the chord structure).

Around that time I was also sometimes mislabeled as jazz, but I also don't play jazz on the piano, as my main temperament is New Orleans R&B, not jazz. (I am inspired some by the jazz traditions, and jazz was my main focus on the organ before I switched to the piano in 1971).

Any other labels, including anything having to do with anything philosophical, or spiritual, or any beliefs, are also not accurate, as I have no interest in those subjects. I just play the songs the best I can, inspired by the seasons and the topographies and regions, and, occasionally, by sociological elements, and try to improve as a player over time.

Guitar Related Questions

- I use John Pearse steel strings, the Slack Key set.

- I never change the strings. And I ask friends (not players that change their strings after every concert, those are virtually new strings) to send me old ones, since in the event of one breaking, putting a new one on would stick out too much.

- I play everything (no matter what key) in the G Major Tuning on a 1965 Martin D-35 Dreadnought (no cutaway, and with the body meeting the neck at the 14th fret), with a low pitched 7th string added, off the fretboard ([C]-D-G-D-G-B-D - from the lowest pitched string to the highest), and for more power and getting the Curt Bouterse 1800 banjer "thwank", I tune up one half step to sound in the key of A flat, or two half steps to sound in the key of A (or in between - whatever the strings want at the time. I never play with anyone, so the pitch is not a problem).

- I also occasionally use a smaller Martin D-18, probably made in the 1960s. I tune it (7 stings on that guitar also) to two tunings: [C]-F-G-C-G-B-D (from the lowest pitched string to the highest), and occasionally to the Hawaiian Slack Key tuning, Samoan C Mauna Loa ([C]-F-G-C-G-A-E), only having to change the two highest pitched strings. I also never change the strings and also tune up one or two half steps (or in between).

- If I play open (unfretted) strings as much as possible with chords and especially with melodies and fills. I heard this technique wonderfully played by guitarists Pierre Bensusan, Jerry Reed, Chet Atkins, Phil deGruy, Alex DeGrassi , and by banjo player Bill Keith.

- On the Martin D-35, I never tune to another tuning (except occasionally I tune the lowest pitched 7th string down to A or G), and I don't loosen them for airplane rides (I DO put something between the headstock and the case to prevent 'whiplash'. I also have a strong guitar case and handle, and have it covered with a custom-made big loose cover made by seamstress (and great fiddler) Betty Vornbrook, and I stuff clothes in the cover, both protecting the guitar and making the suitcases lighter (one time in a plane before taking off I saw a forklift run over the guitar - I was not concerned, and the only damage was to the cover - I have 3 of them).

- I never use a DI (an electronic direct input. I took them out of the guitars I have, for me they interfere with the natural acoustics inside the guitar, and I have never liked the sound of them for the way I play and there is one less thing to go wrong). I use one Josephson condenser mic (It needs phantom power, I carry a portable one to occasionally use), pointing the mic to about where the neck of the guitar meets the body. I prefer no mic for solo guitar concerts (and solo harmonica concerts) if the hall is small enough (I never mic the piano for concerts or solo piano dances).

- Playing the piano wears away the nails, so I play with finger tips. I cut nails that grow too long, and I cut the right hand calluses that get too hard and make notes stick out too much.

- I use humidifying granules inside the guitar case to keep the wood from getting too dry. You can get them from Music Sorb at www.musicsorbonline.com and you should replace them once a year.

- Sound Settings: I use 3 settings:

- Weaving through the string on the very right side (making sure especially that the highest pitched string is muted) , I use a cut or torn piece of cardboard from a folder a bit thicker than the ones normally used for file cabinets. I call this the "Baroque Lute Setting".

- Weaving through the string on the very right side (making sure especially that the highest pitched string is muted) , I use a torn playing card about a half inch thick. I call this the "African Setting".

- Played normally with nothing weaved through the strings

I have tried every kind of cardboard and many, many other things - each person would prefer different things to use. I originally got the idea from hearing the great guitarist Ralph Towner use a matchbook in this way around 1981, but didn't really explore it, trying many different textures until recently, in early 2011. In the earlier part of the 20th Century the great South American guitarist Augustine Barrios used steel strings because the hot and humid South American climate deteriorated the gut strings too quickly (nylon strings weren't available yet). To alter the steel string sound, he muted the three highest pitched strings using rubber or eraser material wrapped around each string.

Slack Key is a guitar tradition, like Blues guitar, Flamenco guitar, Jazz guitar, Brazilian guitar, Classical guitar, African guitar, and Folk guitar - it is not a type of guitar. Slack Key can be played on any guitar. I play a 7 string guitar because I wanted an extra low C bass string. Currently I am playing a new Gibson Guitar with a low 7th string added, which is off the fret board, tuned to low C (I sometimes play a 1965 Martin D-35 guitar as well). I mainly use the open G tuning, which is very popular in Hawaii, mainland America, Europe, and it is also played some in the Philippines, and Africa. The tuning from the lowest pitch string, (including the 7th string), to the highest pitched string is [C]-D-G-D-G-B-D. This way I can play in the keys of G and C. I sometimes also play in the key of D, and sometimes I tune the 7th string down to A for songs in the key of D.

I sometimes play in four other tunings:

- [C or F]-C-G-C-G-C-E, known as open C tuning. I am most influenced to play in this tuning by the late American guitarist George Cromarty. I am also inspired in this tuning by the Canadian guitarist Bruce Cockburn, the late American guitarist John Fahey, the late American guitarist Robbie Basho, and multi-instrumentalist Mike Seeger. I am also very inspired by the late Slack Key guitarists Cyril Pahinui and Atta Isaacs who both play extensively in Atta's C Major tuning which has one note different on the fourth string C-G-E-G-C-E.

- [C]-F-G-C-G-B-D, a cross between the G Major Tuning in the top three pitched strings, and the fourth, fifth, and sixth strings are the same as the Samoan Mauna Loa Tuning that the late slack key guitarist Sonny Chillingworth used for the song Let Me Hear You Whisper, on his album SONNY SOLO.

- [C]-F-G-C-G-A-E, known as Samoa Mauna Loa Tuning in Hawai'i. Mauna Loa Tunings are based on a Major chord, with the two top-pitched strings tuned a fifth interval apart. This way, the two highest pitched thinnest strings in a Mauna Loa Tuning can easily be played in sixth intervals (intervals that in most other tunings are played on the highest pitched first string and the third string; or on the second and fourth strings - since in most other tunings most of the highest four pitched strings are tuned a fourth, a Major third, or a minor third interval apart), producing the recognizably sweet sound that Mauna Loa Tunings bring out.

- I also occasionally play a song in the Hawaiian Tuning called G Wahine Tuning: [C]-D-G-D-F# -B-D. Wahine Tunings are tunings that are a Major 7th chord, or tunings that contain a Major 7th note (the Major 7th of the I chord). The open Major 7th note has two functions: it can easily be "hammered on" to produce the tonic note of the I or tonic chord (the note that is the same note as the I chord). Technically, the tuning mentioned above [C]-F-G-C-G-B-D, is a "Wahine" Tuning, since it contains the Major 7th note of the key of C (the B note).

I like to improvise on the guitar in basically two traditions: Hawaiian Slack Key, and Appalachian/ American folk music. I also play an occasional Irish tune, an occasional Standard (especially inspired by the late guitarist Ted Greene), and some compositions and arrangements by contemporary guitarists/composers such as the late songwriter/fiddler/banjo player John Hartford, banjo player Curt Bouterse, harmonica player Rick Epping, guitarist Ralph Towner, the late guitarist George Cromarty, the late Brazilian guitarist Bole Sete, the late country guitarist Jerry Reed, Canadian guitarist Bruce Cockburn and guitarist Walter Boruta.

I sometimes play solo guitar concerts as benefits for service organizations.

Common most used tunings in the world (roughly in order of the frequency of use):- Standard Tuning - E-A-D-G-B-D

- Dropped D Tuning - D-A-D-G-B-E

- Open G Tuning (aka Taro Patch Tuning; aka Spanish Tuning) - D-G-D-G-B-D

- Open D Tuning - D-A-D-F#-A-D

- Dad Gad Tuning (aka D Modal Tuning) - D-A-D-G-A-D

- G Sixth Tuning - D-G-D-G-B-E

- Dropped C Tuning (aka Keola's C Tuning) - C-G-D-G-B-E

- C Major Tuning - C-G-C-G-C-E

Ted Greene was a wonderful guitarist and educator, he was best known for his book Chord Chemistry and for his wonderful recordings of solo guitar that I'm still learning from after hearing it in 1978. Ted's main influences were the late jazz guitarist George Van Eps, Wes Montgomery, Lenny Breau, and many film soundtrack composers such as the late Max Steiner, the late George Duning, and many, many more. Ted played with a deep feeling for every song he played and extending the beauty of those songs with what he called "extended diatonic" harmony, and more.

Statement by George Winston at the John Fahey Memorial on March 4, 2001.

"John Fahey has been, is and will continue to be a great influence on music as we know it - as a solo guitarist, a composer, and as an independent label owner & producer. He started his own label, Takoma Records, in 1958 to record his unique solo guitar compositions, which was unheard of at the time. His other great contributions include locating some of the great pre-war country blues guitarists from the South, such as Bukka White (Parchment Farm), Robert Pete Williams and Skip James (I'm So Glad). He was also instrumental in locating many old recordings of these great musicians for re-issue so we could all be inspired by them, especially those of great Mississippi bluesman Charley Patton, the main inspiration for Robert Johnson. And he brought forward the great solo guitar artistry of the late Brazilian guitarist Bole Sete. And he issued albums on his Takoma label of the great contemporary guitarists Leo Kottke, the late Bola Sete, the late Robbie Basho, Rick Ruskin and Peter Lang. And he was also a great writer. The list goes on. It is a very long story. I would need 5 books to tell it, but suffice to say things would be very different without him and he was my very dear friend, and the world is very different without him here.

I would not be doing anything that I am doing now--solo piano albums, solo instrumental concerts, and recording the great solo Hawaiian slack key guitarists on my own label - without his influence and inspiration. And he is the only person in the world who would have recorded me as a solo pianist in 1972, which paved the way for all that I do now. I thank you John, but just knowing you, or hearing you would have been great enough.

I share with all of you here a love of the whole person, of which his great unique music is just a part, as you all well know. We will never see the likes of one like him again. And I had the supreme privilege of knowing him for 30 years.

He taught us to be ourselves--even not to even care what he thought---but in the end what he thought always DID matter to us anyway, didn't it? We never know if he was going to attack or tolerate our nonsense. The lingering problem, besides not being able to hear him play or hang out with him to hear his slant on history, music, many other subjects (and on what was happening right there IN THE MOMENT), is: how do we explain him to the uninitiated???

One of the greatest things about knowing John, and there were many things, was that I appreciate the individually of everyone else more. Everyone has this great things in them, even if it is covered and repressed by societies, groups, etc. Nothing ever stopped him for a second. May we all become ourselves. He was and is a teacher, maybe even more so because he didn't claim to be one. I owe much to many, but without question, he changed my life more than anyone else. Aloha John, and to all of you. Thank you all for loving him too."

If I had to name one song, it would be the South African song Isoka Labaleka, played as an instrumental acoustic guitar solo by the great Blind Man and His Guitar, as is listed on the 78 RPM record. He played the melody and the bass simultaneously, while answering the melody phrases with a drone phrase with two strings playing the same note. He is probably playing in the G Major tuning (D-G-D-G-B-D, from the lowest pitched string to the highest), tuned up a half step to the key of A Flat (even though this tuning is not common in Africa). He accomplishes all this by playing just the five highest pitched strings, never playing the lowest pitched six string. It is so powerful and moving and I can feel his humanity and his very soul and he creates a whole encyclopedia and a whole world in three minutes.

This track was originally recorded on a South African 78 RPM record, year unknown. I know of no other recording by this artist. I wish more than anything that more could have been recorded on him. This track changed my perspective on everything.

Another candidate would be the great blues/jazz guitarist Lonnie Johnson's song from 1926, To Do This You Got To Know How.

Another candidate would be the 1949 version of Hey Now Baby by the late New Orleans R&B pianist Professor Longhair, from his album NEW ORLEANS PIANO (Atlantic 7225), and which features many of his signature techniques, including beautiful right hand triplets and rolls, left and right hand syncopations, and left hand puch beats. This track also changed my perspective on everything.

Another candidate is the 1976 version of Pixie, by the late New Orleans R&B pianist James Booker, from his album JUNKO PARTNER (Rykodisk 1359), featuring many of his beautiful signature techniques, and also reflects the Professor Longhair influence. To me this song totally captures the feeling of the heat rising off the pavement on a sweltering summer day.

Harmonica Related Questions

I often use Hohner Big River harmonicas, in the key of low D (using Hohner Low D Cross Harp reed plates within the Big River Harmonica body (these both are unavailable now, so I would use the Hohner Thunderbird harmonica, key of Low D if I needed to order more).I also use the Hohner Big River harmonicas in the key of A. I usually play solo harmonica pieces in these three keys (referenced here on a C harmonica for convenience:

- the 1st position key, playing in the key of C (the Major scale - C, D, E, F. G, A, B C);

- the 2nd position, playing in key of G (the Mixolydian mode - G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G), called "cross harp" playing;

- and the 3rd position, playing in the key of D Minor (the Dorian mode - D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D).

(The 2nd position cross harp playing, in the key of G on a C harmonica, is by far the most common way of playing by harmonica players in America).

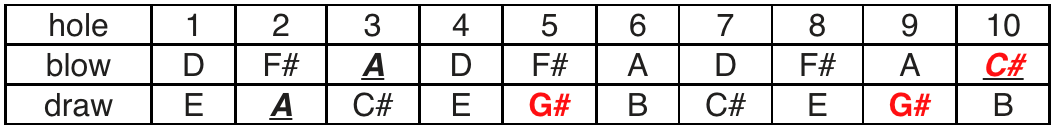

I most often play the 10 hole harmonicas in the low key of D in the 2nd position for playing in the key of A, and for that I tune the holes 5 & 9 draw up a half step, as well as tuning hole 10 blow down a half step.

I learned how to tune harmonicas from the great harmonica player Rick Epping, and he invented the tuning with holes 5 & 9 tuned up a half step, so you could play in the 2nd position with the Major 7th note available (rather than the flatted 7th note that is there in the Standard harmonica tuning.

- and Lee Oscar Harmonicas also offers tuning kits and directions on tuning and retuning the harmonica), as well as tuning hole 10 blow down a half step.

- It is best to practice tuning and re-tuning on old harmonicas at first, since it is easy to make damaging mistakes when you first start learning to

More recently Rick Epping has made me 12 hole harmonicas with an extra high hole and an extra low hole, making 4 more notes available to play.

Here is the main tuning I use : both on a 10 hole harmonica, and then on a 12 hole harmonica (noted on key of D harmonicas):

- for the Major scale in the 2nd position – THIS IS THE MAIN TUNING I USE - based on the Rick Epping “5&9 Draw Raised Notes Tuning” (notes in red are ones altered from the Standard tuning):

- Low D 10 hole harmonica

A. for playing in the 2nd position, in the key of A, in the Major scale - single Richter (for playing the 1st note of the scale as a low drone on hole 2 draw & hole 3 blow with the melody higher than that).

– chords (or partial chords) available in this position are the A Major chord (the I chord), the C# minor chord (the iii chord), the D Major chord (the IV chord), the E Major chord (the V chord), and the F# minor (the vi chord).

B. also for playing in the 3rd position, in the key of E, in the Mixolydian Mode (Major scale with flatted 7th note) - single Richter (for playing the 4th note of the scale as a low drone on hole 2 draw & hole 3 blow with the melody higher than that).

- chords (or partial chords) available in this position are the E Major chord (the I chord), the F# minor chord (the ii chord), the A Major chord (the IV chord), the C# minor chord (the vi chord), and the D Major chord (the VII chord).

C. also for playing in the 5th position, in the key of F# minor, in the Aeolian Mode (minor scale with flatted 3rd, 6th, & 7th notes) - single Richter (for playing the 3rd note of the scale as a low drone on hole 2 draw & hole 3 blow with the melody higher than that) – for playing “Butterfly Jig”

– chords (or partial chords) available in this position are the F# minor chord (the I chord), the C# minor chord (the v chord), the D Major chord (the VI), and the E Major chord (the VII chord).

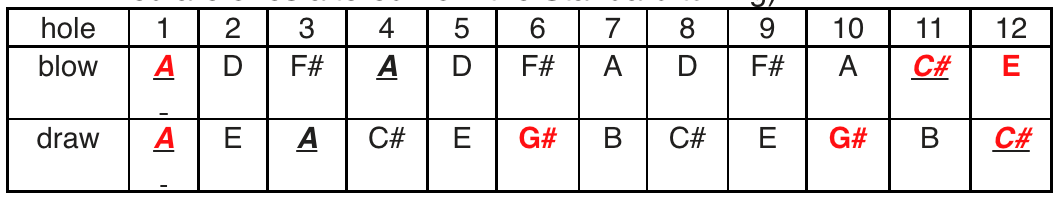

- Also I often play the same tuning expanded on a twelve hole harmonica, with 2 extra holes, yielding 4 extra notes (again, notes in red are ones altered from the Standard tuning):

I also often use a Low D 12 hole harmonica, made for me by Rick Epping – Here again the tuning based on the Rick Epping “5&9 Draw Raised Notes Tuning” on a 10 hole harmonica (they are holes 6 & 10 on this 12 hole harmonica) -

A. for playing in the 2nd position, in the key of A, in the Major scale - triple Richter (for playing the 1st note of the scale as a very low drone on hole 1 blow & draw with the melody higher than that; and for playing the 1st note of the scale as a low drone on hole 3 draw & hole 4 blow with the melody higher than that; and for playing the 3rd note of the scale as a high drone on hole 11 blow & hole 12 draw with the melody lower than that).

– chords (or partial chords) available in this position are the A Major chord (the I chord), the C# minor chord (the iii chord), the D Major chord (the IV chord), the E Major chord (the V chord), and the F# minor (the vi chord).

B. also for playing in the 3rd position, in the key of E, in the Mixolydian Mode (Major scale with flatted 7th note) - triple Richter (for playing the 4th note of the scale as a very low drone on hole 1 blow & draw with the melody higher than that; and for playing the 4th note of the scale as a low drone on hole 3 draw & hole 4 blow with the melody higher than that; and for playing the 6th note of the scale as a high drone on hole 11 blow & hole 12 draw with the melody lower than that).

- chords (or partial chords) available in this position are the E Major chord (the I chord), the F# minor chord (the ii chord), the A Major chord (the IV chord), the C# minor chord (the vi chord), and the D Major chord (the VII chord).

C. also for playing in the 5th position, in the key of F# minor, in the Aeolian Mode (minor scale with flatted 3rd, 6th, & 7th notes) - triple Richter (for playing the 3rd note of the scale as a very low drone on hole 1 blow & draw with the melody higher than that; and for playing the 3rd note of the scale as a low drone on hole 3 draw & hole 4 blow with the melody higher than that; and for playing the 5th note of the scale as a high drone on hole 11 blow & hole 12 draw with the melody lower than that).

– chords (or partial chords) available in this position are the F# minor chord (the I chord), the C# minor chord (the v chord), the D Major chord (the VI), and the E Major chord (the VII chord).

For other harmonica tunings I use, and tunings in general see question # 8 below.

I play extra notes - octaves, double notes, and chords wherever possible, since I am always playing solo. I get these by what is called "tonguing", which means to put the front of the tongue on the harmonica, blocking certain holes so they don't sound. Then when you lift your tongue off those holes a cord will sound. This is the way to play the melody with the right side of the month accompanied by a chord.

To get the "stride harmonica" with a bass and chord and melody, playing in the the first position (the key that is stamped on the harmonica) - play a low note with the left side of the mouth on the first beat of the measure while the tongue is in the middle of the harmonica blocking notes. Then you play out of both sides of the month with the low note on the left side of the month on the first beat of the measure, then release the tongue on the second beat to produce the chord. Place the tongue back again on the harmonica on the third beat, while playing out of the left side of the mouth for another bass note, then release the tongue for the fourth beat, getting another chord. The right side of the mouth plays the melody while this is happening.

A good way to practice getting a bass note with the left side of the mouth and a melody note with the right side of the mouth is to practice octaves in the low part of the harmonica, for example, blowing out with the breath and blocking holes 2 and 3 with the tongue and playing holes 1 and 4 with the left and right side of the month respectively. You can hold this octave and lift the tongue on and off the harmonica, and then the next step would be to practice playing the note with the left side of the month on beats one and three, and then lifting the left side of the mouth off the harmonica along with lifting the tongue off the harmonica on beats two and four.