- Essays by George Winston

- George Winston Music Files

- Essays by Others

- Music Archives by Others

- New Orleans R&B Piano

- Jazz & Melodic Piano

- Hawaiian Slack Key Guitarists

- Other Guitarists

- Harmonica: Appalachian/Old Time Country, Cajun, Celtic, & related influences

1. Essays by George Winston

Extended liner notes from George's album NIGHT DIVIDES THE DAY - THE MUSIC OF THE DOORS - Click here

Extended liner notes from George's album LINUS & LUCY - THE MUSIC OF VINCE GUARALDI VOL. 1 - Click here

Extended liner notes from George's album LOVE WILL COME - THE MUSIC OF VINCE GUARALDI - VOL. 2 - Click here

WEBSITES ON VINCE GUARALDI:

- www.georgewinston.com - For extended liner notes, Vince Guaraldi’s complete discography, videos & more, and a great 1981 article on Vince by Bob Doerschuk for Keyboard Magazine , and more, go to www.georgewinston.com, then to ‘Albums’, then to “LINUS & LUCY–THE MUSIC OF VINCE GUARALDI – Vol. 1”, then to then to ‘liner notes’, then to ‘websites’, & then you can download a PDF or read online. You can also see the notes to George’s album LOVE WILL COME–THE MUSIC OF VINCE GUARALDI – Vol. 2.

- www.anatomyofvinceguaraldi.com - The official site of the documentary film THE ANATOMY OF VINCE GUARALDI, produced in 2009 and 2010 by filmmakers Andrew Thomas and Toby Gleason. This is the new updated version with bonus footage of the film ANATOMY OF A HIT, a three-part film about Vince’s song Cast Your Fate to the Wind, produced by Toby’s father Ralph J. Gleason for PBS TV in 1963. The beginning of the film is based on ANATOMY OF A HIT, and then Vince's story moves forward through his years at the hungry i, to his Jazz Mass at Grace Cathedral, and his scores for the first 16 of the PeanutsÒ animations. This feature-length film blends newly discovered recordings and film with the on-screen insights of Dave Brubeck, Dick Gregory, Jon Hendricks, George Winston, and others, making it an essential resource for anyone with an interest in Vince Guaraldi.

- www.vinceguaraldi.com - The official Vince Guaraldi family site - the Guaraldi family is constantly issuing new recordings on the family label, D&D Records.

- www.schulzmuseum.org - Site for the Charles Schulz Museum

- www.snoopy.com - the official Peanuts Worldwide site

Author/researcher Derrick Bang’s sites: - http://impressionsofvince.blogspot.com -Derrick Bang has written a wonderful deeply informative book: VINCE GUARALDI AT THE PIANO. He has also written several books on PeanutsÒ creator Charles Schulz. For updates to the book see http://impressionsofvince.blogspot.com - In Derrick’s words, “This blog is a detailed companion to my published career study, Vince Guaraldi at the Piano. Even at close to 400 pages, the book wasn't long enough to permit the inclusion of every significant event, performance or recording date during Vince Guaraldi's quite busy lifetime. Additionally, a project of this nature never really ‘concludes’, because new information always comes to light; this blog will serve as the perfect home for such fresh material. Any visitors with additional information are asked to contact me at derrick@fivecentsplease.org.”

-

http://fivecentsplease.org/dpb/VinceGuaralditimeline.html - VInce Guaraldi timeline.

-

http://fivecentsplease.org/dpb - Derrick Bang’s great site on PeanutsÒ, Charles Schulz, and Vince Guaraldi, including a complete discography (click on “Music” on the left side or go right to http://fivecentsplease.org/dpb/guaraldi.html).

-

http://fivecentsplease.org/dpb/cuesheet.html - Itemized list of all Vince Guaraldi compositions in the 16 PeanutsÒ animations on Derrick Bang’s site

VINCE GUARALDI DISCOGRAPHY: (these are in print unless otherwise noted - and the year the album was recorded is listed at the end of each selection):

AS A LEADER:

- A CHARLIE BROWN CHRISTMAS (Fantasy FCD-30066-2) – “Super Deluxe” five-disc edition released in 2022, with a new stereo mix and five complete studio sessions — with multiple alternate versions, incomplete takes and studio chatter — that demonstrate how these iconic songs evolved, as Vince Guaraldi decided how to shape them; includes new liner notes by Guaraldi biographer Derrick Bang. This release supersedes the 2012 “Snoopy Doghouse Edition,” with three bonus tracks; and a 2006 edition with five different bonus tracks (all of which are included in the 2022 mega-edition). Also see www.peanutscollectorclub.com/cbxmas.html – this classic album was originally released in 1965. In addition to the original stereo mixes of the original album tracks, and new 2022 mixes of the original album tracks, and many outtakes of Christmas is Coming, Christmas is Coming, Skating, Linus and Lucy, O Tannenbaum, , Fur Elise, Greensleeves, and The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on the Open Fire).and more.

- IT’S THE GREAT PUMPKIN, CHARLIE BROWN (Craft Recordings CR00565) — 2022 release(not to be confused with the inferior 2018 release), of tracks that were previously thought lost to time, with remastered tracks from the original studio sessions reels for this TV special, as recorded by Vince Guaraldi and his trio, before the cues were edited down for insertion into the show. It includes numerous bonus tracks and alternate takes of the most iconic themes, and new liner notes by Guaraldi biographer Derrick Bang.

- JAZZ IMPRESSIONS OF BLACK ORPHEUS [aka CAST YOUR FATE TO THE WIND] (Original Jazz Classics OJC-437-2) – has the original version of Cast Your Fate to the Wind – originally issued in 1962 – reissued in 2010 with 5 bonus tracks, including an alternate take of Cast Your Fate to the Wind. In 2022 this album was reissued as a 2 disk set with the title JAZZ IMPRESSIONS OF BLACK ORPHEUS, with bonus tracks of outtakes for every song, including 3 alternate takes of Cast Your Fate to the Wind.

-

OH, GOOD GRIEF! (Warner Bros. Records WS 1747) – 1968

-

ALMA-VILLE (Wounded Bird Records WOU-1828 [formally on Warner Brothers Records]) - 1970

-

THE ECLECTIC VINCE GUARALDI (Wounded Bird Records WOU-1775 [formally on Warner Brothers Records) -1969

-

THE COMPLETE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS RECORDINGS (Omnivore OV-288) — a wholly re-mastered two-disc set gathering the 26 tracks from the albums OH, GOOD GRIEF!, THE ECLECTIC VINCE GUARALDI and ALMA-VILLE, plus four bonus tracks including a Guaraldi original “The Share Cropper’s Daughter.” Also includes new liner notes by Guaraldi biographer Derrick Bang.

-

THE CHARLIE BROWN SUITE & OTHER FAVORITES (RCA Bluebird 82876-53900) – live concert with an orchestra from May 18, 1968, along with three studio tracks from the 1960s – (Two of this album's track are mis-identified: The track called "Happiness Is," which is one of the interior movements within "The Charlie Brown Suite," is actually "The Great Pumpkin Waltz"; and the track called "Charlie Brown Theme" is actually "Oh, Good Grief")

-

CHARLIE BROWN’S HOLIDAY HITS (Fantasy 9682-2) - (Four of this album's tracks are mis-identified: The track called "Joe Cool" is not composed by or played by Vince Guaraldi, but is actually is a mash-up of two short cues by Ed Bogas and Desiree Goyette, from "The Charlie Brown and Snoopy Show"; and song called "Track Meet" actually is a variant arrangement of "Christmas Is Coming"; and the track called"Oh, Good Grief" actually is a vocal version of "Schroeder"; and finally,"Surfin' Snoopy" is an alternate title for the cue originally titled "Air Music") - – tracks from the 1960s and 1970s

-

PEANUTS GREATEST HITS (Fantasy Records) - tracks from the 1960s and 1970s

-

PEANUTS PORTRAITS (Fantasy Records FAN-31462) – Full versions of ten songs from the Peanuts soundtracks (they are usually much shorter in the episodes, to match the action), as well as unissued versions of Frieda (with the Naturally Curly Hair), Schroeder, Blue Charlie Brown, Charlie’s Blues, and Sally’s Blues, and Vince’s great vocal on Little Birdie. – issued in 2010

-

VINCE GUARALDI AND THE LOST CUES FROM THE CHARLIE BROWN TV SPECIALS (D&D Records VG 1118 - 2006

-

VINCE GUARALDI AND THE LOST CUES FROM THE CHARLIE BROWN TV SPECIALS – VOLUME 2 (D&D Records VG 1119) - 2008

-

THE GRACE CATHEDRAL CONCERT [aka VINCE GUARALDI AT GRACE CATHEDRAL] (Fantasy FCD-9678-2) - 1966

-

JAZZ IMPRESSIONS OF BLACK ORPHEUS (Original Jazz Classics OJC-437-2) – has the original version of Cast Your Fate to the Wind – originally issued in 1962 – reissued in 2010 with 5 bonus tracks, including an alternate take of Cast Your Fate to the Wind.

-

NORTH BEACH (D&D Records VG 4465) – tracks from the 1960s

-

OAXACA (D&D Records VG 1125) – tracks from the late 1960s and early 1970s

-

VINCE GUARALDI TRIO – LIVE ON THE AIR (D&D Records VG1120 – live tracks from 1974

-

AN AFTERNOON WITH THE VINCE GUARALDI QUARTET – (VAG Publishing LCC - VAG 1121) – live tracks from 1967

-

VINCE GUARALDI WITH THE SAN FRANCISCO BOYS CHORUS (D&D VG 1116) – 1968

-

A BOY NAMED CHARLIE BROWN [film soundtrack] – A BOY NAMED CHARLIE BROWN [film soundtrack] – limited edition issued in 2017 – here is a excerpted and paraphrased description by Derrick Bang from his website [http://impressionsofvince.blogspot.com/2017/03/ and http://impressionsofvince.blogspot.com]: The specialty soundtrack label Kritzerland, known for its prestige handling of expanded, long unavailable and/or previously unreleased scores, has produced a full-score album of the Academy Award-nominated music from the 1969 film A Boy Named Charlie Brown.

And it features lots of previously unavailable Guaraldi tracks, along with all the clever Rod McKuen songs, and John Scott Trotter’s supplemental orchestral cues, as heard in the film, and in gloriously clear stereo sound. But wait, there’s more: The disc also includes a bunch of nifty bonus tracks, allowing some of Guaraldi’s best work to shine, notably with extended versions of “Skating” and “Blue Charlie Brown”. (It should be noted — for archivists who pay attention to such things — that this now is the third album with this title, and is distinct from Guaraldi’s 1964 Fantasy album, and Rod McKuen’s 1970 Stanyan Records album.)

Additional information about this new release can be found at Kritzerland’s web site [http://www.kritzerland.com/boy_charlie_brown.htm and http://www.kritzerland.com] (No, it won’t be available via Amazon, nor will it ever pop up in a brick-and-mortar store.) Bear in mind, as well, that this is a limited-issue release of 1,000 copies. Some previous releases have sold out in a matter of weeks or even days, so don’t delay. [Update on March 24, 2017: It sold out in a week – hopefully more will be available].

- (it was previously issued on LP in 1969 on Columbia Masterworks OS3500, as an edited shorter version of the dialogue and music from the film).

-

THE LATIN SIDE OF VINCE GUARALDI (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-878-2) - 1964

-

JAZZ IMPRESSIONS (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-287-2) - 1957

-

A FLOWER IS A LOVESOME THING (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics OJC-235-2) - contains five tracks from the album JAZZ IMPRESSIONS, along with three other tracks - 1957

-

VINCE GUARALDI-IN PERSON (Fantasy Original Jazz Classical OJCCD-951-2) - 1963

-

VINCE GUARALDI TRIO (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-149-2) – 1956

-

JAZZ SCENE: SAN FRANCISCO (MODERN MUSIC FROM SAN FRANCISCO) (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics 272 – the LP is out of print, and the 1991 reissued CD titled THE JAZZ SCENE SAN FRANCISCO on Fantasy 24760 is also out of print) - has two tracks by The Vince Guaraldi Quartet, as well as three tracks with Vince playing with the Ron Crotty Trio – 1955

Compilations of songs from previous Vince Guaraldi albums:

-

VINCE GUARALDI’S GREATEST HITS (Fantasy 7706-2) – 1980

-

THE DEFINITIVE VINCE GUARALDI (Fantasy Records FAN 31462) – 2 CD set of tracks from his Fantasy Label recordings from 1955 through 1965, including two previously unissued bonus tracks, Autumn Leaves, and Blues for Peanuts.

-

ESSENTIAL STANDARDS - (concord OJC31426 02) – compilation of songs from eight albums – 2009

VINCE GUARALDI WITH BOLA SETE:

-

VINCE GUARALDI, BOLA SETE & FRIENDS (Fantasy 8356) – with guitarist Bola Sete - 1963

-

LIVE AT EL MATADOR (Original Jazz Classics OJC-289) – with guitarist Bola Sete – 1966

- these two albums, VINCE GUARALDI, BOLA SETE & FRIENDS and LIVE AT EL MATADOR have been reissued together on one CD as VINCE GUARALDI AND BOLA SETE (Fantasy FCD-24256-2)

-

FROM ALL SIDES (Original Jazz Classics OJC 989) - with guitarist Bola Sete - 1965

-

VINCE GUARALDI & BOLA SETE - THE NAVY SWINGS (VAG Publishing LCC – live radio broadcasts of Vince’s trio with guitarist Bola Sete - 1965

-

JAZZ CASUAL: PAUL WINTER/ BOLA SETE & VINCE GUARALDI (Koch Jazz KOC CD-8566) – Vince’s trio with guitarist Bola Sete (the Paul Winter set, without Vince, is a separate performance) - this performance by Vince and Bola is also on DVD: JAZZ CASUAL: ART PEPPER/ VINCE GUARALDI & BOLA SETE (the Art Pepper set, without Vince, is a separate performance) - produced by Ralph J. Gleason for PBS TV in the mid 1960s – (the DVD issue of the original Rhino Home Video VHS release is out of print but is sometimes available used at Amazon.com – if ordering for North American DVD players, be sure to order the NTSC version) – 1963

VINCE GUARALDI AS A SIDEMAN (in print unless otherwise noted):

- WITH CAL TJADER:

-

EXTREMES (Fantasy FCS-24764-2) – reissue contains two albums: THE CAL TJADER TRIO, recorded with Vince Guaraldi in 1951; and the album BREATHE EASY (without Vince) - 1951

-

CAL TJADER LIVE AT THE CLUB MACUMBA (Acrobat Records [UK release]) - 1956

-

CAL TJADER: OUR BLUES (Fantasy FCD-24771-2) – reissue contains two albums: CAL TJADER, recorded with Vince in 1957; and CONCERT ON THE CAMPUS ( without Vince) – 1957

-

JAZZ AT THE BLACKHAWK (Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-436-2) – 1957

-

BLACK ORCHID (Fantasy FCD-24730-2) – reissue contains two albums: CAL TJADER GOES LATIN, recorded with Vince in 1957; and CAL TJADER QUINTET (without Vince) - 1957

-

SESSIONS LIVE: CAL TJADER AND CHICO HAMILTON (Calliope CAL 3011 - LP only, and out of print) - Vince plays on four songs with Cal Tjader: Lover Come Back to Me, The Night We Called It a Day, Bernie’s Tune, and Jammin’ – 1957

-

LOS RITMOS CALIENTES (Fantasy FCD 24712-2) –reissue contains two albums: MAS RITMO CALIENTES, RECORDED WITH Vince in 1957; and RITMO CALIENTE (without Vince) - 1957

-

SENTIMENTAL MOODS (Fantasy FCD-24742-2) – reissue contains two albums: LATIN FOR LOVERS, recorded with Vince in 1958; and SAN FRANCISCO MOODS, which includes only one track with Vince, recorded in 1958 - 1958

-

A NIGHT AT THE BLACKHAWK [reissue of the album BLACKHAWK NIGHTS] (Fantasy OJCCD-2475-5) – 1958

-

CAL TJADER’S LATIN CONCERT [reissue of the album LATIN CONCERT] (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-643-2) – 1958

-

SESSIONS LIVE: CAL TJADER, CHRIS CONNOR AND PAUL TOGIWA (Calliope CAL 3002 - LP only, and out of print) – Vince plays on three songs: Crow’s Nest, Liz-Anne (aka Leazon), and Tumbao - 1958

-

CAL TJADER/ STAN GETZ QUARTET (aka THE STAN GETZ/ CAL TJADER QUARTET) [reissue of the album STAN GETZ WITH CAL TJADER] (Fantasy Original Jazz Classics OJCCD-275) – 1958

-

BEST OF CAL TJADER: LIVE AT THE MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL 1958-1980 (Concord/ Monterey Jazz Festival Records MJFR-30701 ) - Vince plays on the first four tracks from the legendary performance from 1958: especially on Summertime and Now’s the Time; and also Cubano Chant, and Tambao – 1958

- WITH WOODY HERMAN:

-

WOODY HERMAN AND HIS ORCHESTRA: 1956 Storyville Records [Denmark] STCD 8247/48 – Double CD set with 41 songs with Vince Guaraldi as past of the Woody Herman Big Band, recorded July 28-29, 1956 – Here Vince piano wasn't recorded very well, so you need to boost the volume to best hear his introductions and his playing (and turn it down when the other instruments kick back in). He can be heard at the beginning of These Foolish Things, Buttercup, After Theater Jump, and Pimlico. Vince plays some short solos midway through Autobahn Blues and Square Circle, and he plays a bit more during Woodchopper's Ball. Vince’s best playing on these CDs is on five other tracks: Opus De Funk, which starts with his great boogie-woogie solo that runs for about a minute; Country Cousin, where he plays a brief intro and then a long solo halfway through the song; Wild Root, which has a great Vince solo; and best of all on Pinetop's Blues, with Vince's great boogie-woogie work behind Woody's vocal.

-

THE COMPLETE CAPITAL RECORDINGS OF WOODY HERMAN 1944-56 (Mosaic MD6-196) - 6 CD SET including all the tracks from the BLUES GROOVE album listed just below). Disk 5 has three tracks that feature Vince Guaraldi: 5-10-15 Hours, You Took Advantage of Me, and Wonderful One; the BLUES GROOVE album tracks featuring Vince are Pinetop’s Blues, Blues Groove, and Dupree’s Blues – 1956

-

BLUES GROOVE (Capital T784, LP only - out of print – see # 2 just above) – with Woody Herman – 1956

-

WOODY HERMAN’S ANGLO-AMERICAN HERD (Jazz Groove #004 - LP only, and out of print) - recorded live in Manchester, England, in April 1959 – 1959

- WITH OTHERS:

1. GUS MANCUSO & SPECIAL FRIENDS (Fantasy FCD-24762-2) – contains two albums: INTRODUCING GUS MANCUSO, recorded in 1956 with Vince; and GUS MANCUSO QUINTET (without Vince) – 1956

2. WEST COAST JAZZ IN HIFI (Fantasy OJCCD-1760-2) - [originally issued with the title JAZZ EROTICA {Hi Fi Jazz –R-604}] – with Richie Kamuca & Bill Holman - 1957

3. THE FRANK ROSOLINO QUINTET (VSOP #16-CD – reissue of the album called VINCE GUARALDI/ FRANK ROSOLINO QUINTET on Premier Records PS 2014, and also issued on Mode Records MOD-LP-107; reissued on CD in Japan on the Muzak, Inc. Label MZCS-1166 – and four tracks from this album also appear on the album NINA SIMONE LIVE –WITH SPECIAL GUEST VINCE GUARALDI (Coronet CXS 242 – LP only) Vince appears on 4 tracks with the Frank Rosolino Quintet, and these are entirely separate from the Nina Simone tracks) - with Frank Rosolino – 1957

4. LITTLE BAND, BIG JAZZ (Fresh Sound Records FSR1629) – [aka VINCE GUARALDI AND THE CONTE CANDOLI ALL STARS] (Crown Records CST417 & CLP5417) – with Conte Candoli – 1960

-

CONTE CANDOLI QUARTET (Music Visions TFCL-88915 [Japan issue] – reissue of the album THE VINCE GUARALDI/CONTE CANDOLI QUARTET on Premier Records PM 2009, and also issued on Mode Records MOD-LP-109; reissued on CD in Japan on the Muzak, Inc. Label MZCS-1167) – 1957

-

MONGO (Prestiege PRCD 24018-2 – reissue has the albums MONGO and YAMBU) – with Mongo Santamaria – Vince plays on one song from the MANGO album, Mazacote - 1958

-

LATINSVILLE! (Contemporary CCD-9005-2) – with Victor Feldman - 1959

-

BREW MOORE QUINTET (Fantasy OJCCD-100-2 [F-3-222]) – with Brew Moore – Vince plays on one song, Fools Rush In - 1955

-

BREW MOORE (Fantasy LP3-265 & Original Jazz Classics OJC 049 - on LP and out of print) – Vince plays on one song, Dues’ Blues -1955

-

JIMMY WITHERSPOON AND BEN WEBSTER (Verve V6-8835) - Vince Guaraldi backs up Jimmy Witherspoon and Ben Webster - 1959

-

LIVE ... JIMMY WITHERSPOON, FEATURING THE BEN WEBSTER QUARTET (EMI/ Stateside SSL 10232 - Vince Guaraldi backs up Jimmy Witherspoon and Ben Webster - 1961

-

JAZZ CASUAL: JIMMY WITHERSPOON AND BEN WEBSTER/ JIMMY RUSHING – produced by Ralph J. Gleason for PBS TV in 1962 – (the DVD issue of the original Rhino Home Video VHS release is out of print but is sometimes available used at Amazon.com - if ordering for North American DVD players, be sure to order the NTSC version) - also available on CD on Koch Jazz KOC CD-8561 – Vince Guaraldi here backs up Jimmy Witherspoon and Ben Webster (the Jimmy Rushing set, without Vince, is a separate performance) – 1962

VINCE GUARALDI VIDEOS:

-

www.anatomyofvinceguaraldi.com – the official site of the documentary film THE ANATOMY OF VINCE GUARALDI, produced in 2009 and 2010 by filmmakers Andrew Thomas and Toby Gleason. This is the new updated version with bonus footage of the film ANATOMY OF A HIT, a three-part film about Vince’s song Cast Your Fate to the Wind, produced by Toby’s father Ralph J. Gleason for PBS TV in 1963. The beginning of the film is based on ANATOMY OF A HIT, and then Vince's story moves forward through his years at the hungry i, to his Jazz Mass at Grace Cathedral, and his scores for the Peanuts® animated programs. This feature-length film blends newly discovered recordings and film with the on-screen insights of Dave Brubeck, Dick Gregory, Jon Hendricks, as well as George Winston, and others, making it an essential resource for anyone with an interest in Vince Guaraldi.

-

JAZZ CASUAL: ART PEPPER/ VINCE GUARALDI & BOLA SETE (the Art Pepper set, without Vince, is a separate performance) - produced by Ralph J. Gleason for PBS TV in 1963 – (the DVD issue of the original Rhino Home Video VHS release is out of print but is sometimes available used at Amazon.com – if ordering for North American DVD players, be sure to order the NTSC version) – also available on CD with the title JAZZ CASUAL: PAUL WINTER/ BOLA SETE & VINCE GUARALDI (the Paul Winter set, without Vince, is a separate performance) on Koch Jazz KOC CD-8566 – Vince here plays with his trio with guitarist Bola Sete, and Bola Sete also appears without Vince -1993

-

JAZZ CASUAL: JIMMY WITHERSPOON AND BEN WEBSTER/ JIMMY RUSHING (the Jimmy Rushing set, without Vince, is a separate performance) – produced by Ralph J. Gleason for PBS TV in 1962 – (the DVD issue of the original Rhino Home Video VHS release is out of print but is sometimes available used at Amazon.com - if ordering for North American DVD players, be sure to order the NTSC version) - also available on CD on Koch Jazz KOC CD-8561 – Vince Guaraldi here backs up vocalist Jimmy Witherspoon and saxophonist Ben Webster – 1962

-

IN THE MARKETPLACE – 1966 documentary about the relationship of churches and society in San Francisco in the mid-1960’s – soundtrack by Vince Guaraldi, who also appears playing some of his music composed for his 1965 Grace Cathedral concert.

-

’67 WEST – documentary about Sunset Magazine, produced by Lee Mendelson with soundtrack by Vince Guaraldi.

-

BICYLES ARE BEAUTIFUL – 1974 educational documentary produced by Lee Mendelson about bicycle safety for kids – soundtrack by Vince Guaraldi.

-

BAY OF GOLD -1965 documentary produced by Lee Mendelson about the history of San Francisco, with some music by Vince Guaraldi. It can be seen online at https://dice.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/205204

-

On July 16,1964 Vince Guaraldi and Bola Sete record some short programs, known as “fills,” for National Educational Television (NET) member stations. They are currently stored at the Library of Congress and not available to see yet.

Two of Vince’s otherwise unrecorded compositions were recorded: Water Street, and Twilight of Youth.

- see Derrick Bang’s post in this in 2021 - http://impressionsofvince.blogspot.com/2021/06/archival-gold.html

Jazz Waltzes - This list is in the web notes for Great Pumpkin Waltz from George's album Linus & Lucy - The Music of Vince Guaraldi; and also in the notes to Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown from George's album LOVE WILL COME - THE MUSIC OF VINCE GUARALDI - VOL 2 (the long list has about 100 songs ).

New Orleans Pianists - (the long list - about 200 pianists) - these are in the web notes for GULF COAST BLUES & IMPRESSIONS - A HURRICANE RELIEF BENEFIT, and for GULF COAST BLUES & IMPRESSIONS 2 - A LOUISIANA WETLANDS BENEFIT.

Instrumentals that George grew up listing to from the 1950's and 1960's - (the long list has hundreds of songs)

Harmonica tunings that George has experimented with for playing solo harmonica (60+ tunings).

Solo harmonica tracks from the 1920's and the 1930's (from anywhere in the world, including America, Ireland, and Australia). George is still working on the notes for each of the 100+ songs.

GREAT SOLO HARMONICA PIECES 1904-2020

-

The keys and tunings of the harmonicas will be listed with each song, as well as the position(s) played in the songs.

-

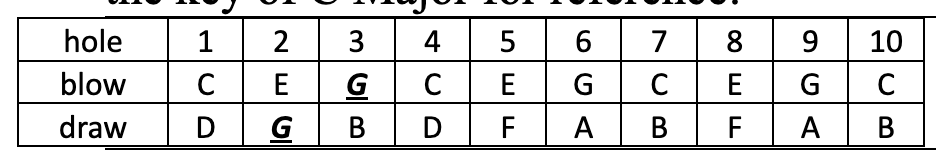

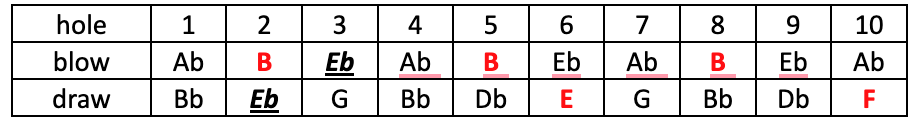

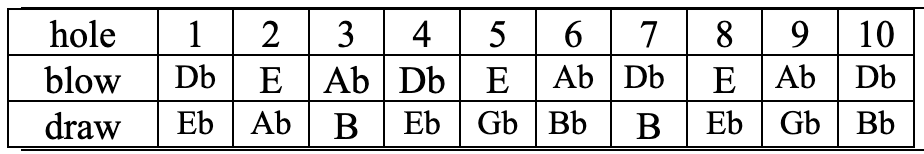

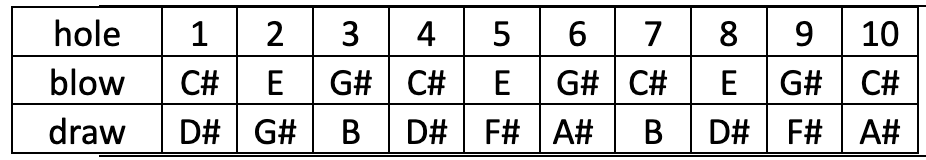

Unless otherwise noted, the songs in this list are played on a 10 hole diatonic harmonica in the Standard Major harmonica tuning - and the other tunings will be indicated within the songs they are in.

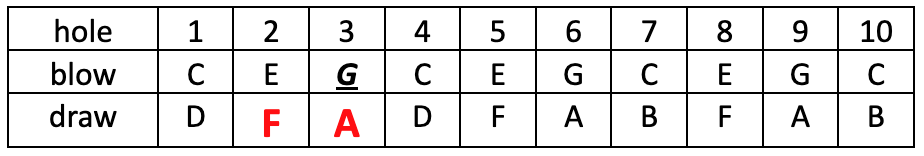

- Here is the Standard harmonica tuning, listed in the key of C Major for reference:

3. If you are looking at this on a phone, you will need to turn the phone on its side to see the whole tuning.

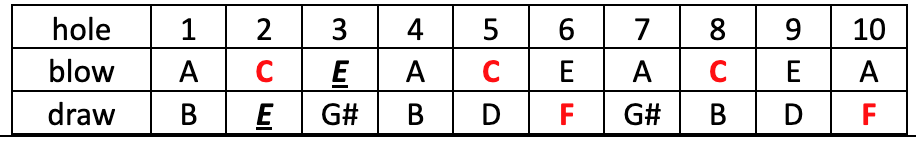

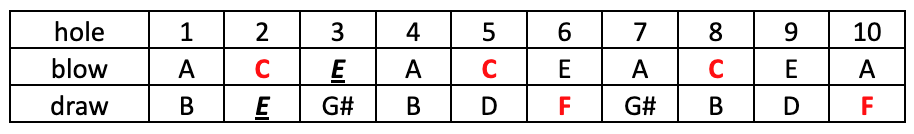

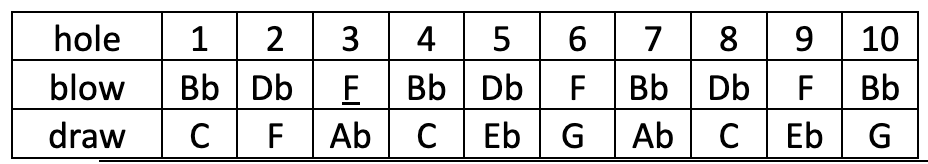

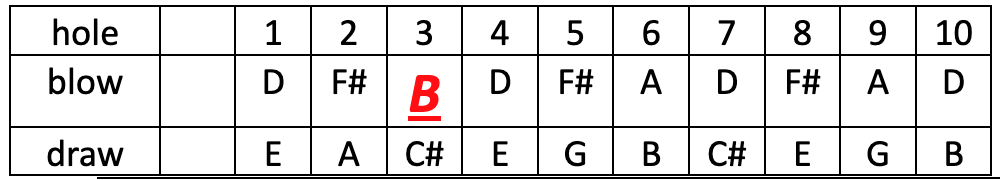

4. Most of the songs in other tunings below are in the Harmonica minor scale (often the key of A minor):

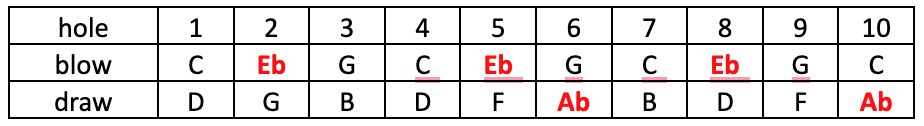

- Here is the key of A harmonic minor harmonica (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of A minor:

(1). notes in red are ones tuned differently from the Standard Major Tuning.

(2). notes that are underlined, slanted, and in bold, are notes that are in the same pitch in both the blow and draw reeds)

(NOTE: This list does include harmonica players Sam Hinton, Rick Epping, or the 16th Street Bluesman, as they are on separate archives of their own).

Deford Bailey:

Deford Bailey(1899-1982), was a well known member of the Grand Ole Opry radio broadcasts from 1927 to 1941 in Nashville, and therefore he probably has been the most influential harmonica player ever. In 2005 the PBS documentary DeFord Bailey: A Legend Lost was aired.

There are also 5 unissued tracks recorded for Victor that have never been found: Lost John, Kansas City Blues, Casey Jones, Wood Street Blues, and Nashville Blues.

Also see the excellent book by David C. Morton and Charles K. Wolfe, DeFord Bailey, A Black Star In Early Country Music, and see http://defordbailey.info/, and http://www.netowne.com/deford/index.htm

And also see his album with tracks recorded 1973-1982 by David C. Morton, DEFORD BAILEY: COUNTRY MUSIC’S FIRST BLACK STAR. The 11 tracks below were recorded in 1927 and 1928.

1927-1928 recordings:

-

Muscle Shoals Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E. This piece especially shows his great tongue blocking technique, wit his playing chords to accompany the melody. -

Pan-American Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Dixie Flyer Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Up Country Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Old Hen Cackle

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A -

The Alcoholic Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Fox Chase

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

John Henry

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Ice Water Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A -

Davidson County Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the key of E & A -

Evening Prayer Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st & 2nd positions in the key of A & E

DeFord Bailey (1974-1976 recordings):

- Pan American

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Ain’t Gonna Rain No More

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A - Alcoholic Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Cow Cow Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the keys of E & A - John Henry

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Old Hen Cackle (take 1)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Old Hen Cackle (take 2)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Sweet Marie

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A - Red River Valley

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A - Gotta See Mama Every Night

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat - Welcome Table

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Shoe Shine Boy

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Swing Low Sweet Chariot

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Hesitation Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E - Saints

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A - Sook Cow Come Get Your Nubbins

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A - Evening Prayer Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the keys of E & A - Fox Chase

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E (Live version from 1973) - Pan American Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E (Live version from 1973) - Shake That Thing

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E (Live version from 1973) - Fox Chase

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E (Live version from 1973)

Kyle Wooten:

Georgia harmonica player, late 1920s recordings.

- Red Pig

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Choking Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A -

Loving Henry

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A -

Fox Chase

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

Violet Waltz

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A -

Lumber Camp Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

El Watson:

American harmonica player, 1927 recordings.

-

Narrow Gauge Blues

- Key of C# harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C# -

One Sock Blues

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G -

Sweet Bunch of Daisies

- Key of F harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of F

Henry Whitter:

American harmonica player, 1927 and 1928 recordings,

-

Rain Crow Bill Blues (1923 version)

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A

Doc Watson grew up hearing Henry Whittier. -

Rain Crow Bill (1927 version)

- Key of D harmonica, played in the position in the key of A -

The Old Time Fox Chase

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G -

Henry Whittier’s Fox Chase

- Key of C harmonica, played in the position in the key of G -

Poor Lost Boy

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Rabbit Race

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F -

Lost Train Blues

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

Hop Out Ladies/ Shortnin’ Bread/ Turkey in the Straw

- Key of E harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of E

William McCoy:

American harmonica player, 1927 recordings.

-

Mama Blues

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G -

Train Imitations and the Fox Chase

- Key of A harmonica, played in the position in the key of A

Chub Parham:

American harmonica player,

-

The Train

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

Gwen Foster

North Carolina harmonica player, late 1920s recording.

-

Wilkes County Blues

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

Gwen also recorded great harmonica on many songs with the Appalachian band the Carolina Tar Heels. This was his only solo harmonica recording.

Freeman Stowers (the Cotton Bell Porter):

American harmonica player, 1929 recordings.

-

Medley of Blues (All Out and Down/ Old Time Blues/ Hog in the Mountain)

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F. -

Railroad Blues

- Key of B flat armonica, played in the 1st and 2nd positions in the keys of B flat and F

George “Bullet” Williams:

American harmonica player, 1928 recordings.

-

Middlin’ Blues

- Key of A flt harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A flat -

Frisco Leaving Birmingham

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Escaped Convict

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

Touch Me Light Mama

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A

Palmer McAbee:

American harmonica player, 1928 recordings.

-

Lost Boy Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E -

McAbee’s Railroad Piece

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st & 2nd positions in the keys of A & #

Jaybird Coleman:

American harmonica player, recordings from the late 1920s and the early 1930s.

-

Mill Log Blues

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Boll Weavel

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Ah’m Sick and Tired of Tellin’ You (to Wiggle That Thing)

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Trunk Busted Blues

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

No More Good Water-Cause the Pond is Dry

- Key of E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A flat -

Mistreatin’ Mama

- Key of E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A flat -

Save Your Money - Lets These Women Go

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A -

Ain’t Gonna Lay My ‘Ligion Down

- Key of A flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A flat -

Troubled About My Soul

- Key of E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of B flat -

Man Trouble Blues

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

You Heard Me Whistle (Oughta Know My Blow)

- Key of E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A flat

Noah Lewis:

American harmonica player, 1930 recordings.

-

Devil in the Woodpile

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G -

Chickasaw Special

- Key of E harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A -

Like I Want to Be

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G

D. H. Bilbro Bert:

American harmonica player, 1928 recordings.

-

C. & N.W. Blues

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st & 2nd positions in the key of B flat and F -

Mohana Blues

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F

Alfred Lewis:

American harmonica player, 1930 recording.

-

Friday Moan Blues (Mississippi Swamp Moan)

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat

Pete Hampton:

1904 tracks, from the BLACK EUROPE 44 CD set collection.

-

Dat Mouth-Organ Coon

-

Mouth-Organ Coon

-

The Mouth organ Coon

-

The Mouth Organ Coon

P. C. Spouce

Australian harmonica player, 1928 and 1929 recordings.

-

Swannee River with Variations

- Key of B harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B -

Medley of Irish Airs (includes Song # 1, Song #2, song 1 again briefly, The Last Rose of Summer, Song #4, and a waltz)

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

The Prisoner’s Song

- Key of B harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B -

Anvil Chorus

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Bluebells of Scotland with Variations

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

March Medley (includes Teddy’s Bear’s Picnic, and other songs)

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of D -

Hornpipe Medley (includes Fisher’s Hornpipe, and 2nd Song, and Fisher’s Hornpipe again, and Soldier’s Joy)

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

Medley of Scotch Reels

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

La Maxixe (Mattchiche)

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of D -

Waltz Medley

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Waltz Memories

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

- He subtly implies bass notes a few places in this 1929 piece, in addition to his tonguing rhythm chords -

Silver Bell

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

Honey, Stay in Your Own Backyard

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C

Elon S. Campbell:

Australian harmonica player, 1920s recordings.

-

Listen to the Mockingbird

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G -

Coocoo Waltz

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G -

Waldmere March

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of c -

Invercargill

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C

Alfred Leslie Benoit:

Australian harmonica player, 1920s recording.

-

Smitty in the Wood/ Annie Laurie

- Key of B harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B

“Professor” Dinkens:

Australian harmonica player, 1920s recordings.

-

Mouth Organ (Medley)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G -

Mouth Organ Medley No 2

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

EF “Poss”Acree

American harmonica player,

-

Chicken Reel

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G (the track is a little flat)\ -

Missouri Waltz

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G (the track is a little flat)

Joseph Sanders

-

La Paloma

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of D (the track is a a little sharp of pitch)

Dick Robertson:

American harmonica player

-

Home Sweet Home

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Red Wing

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat

Freddie L. Small:

108. Tiger Rag

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the keys of G and C

Oliver Sims:

American harmonica player

109.Hop About Ladies

-

Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in key of C.

Emery DeNoyer:

Wisconsin harmonica player, 1941 recording.

-

Snow Deer

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

Mick Conroy:

Irish harmonica player, 1932 recordings.

-

Carmel Mahoney’s Reel

- Key of E harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of E -

The Frieze Breeches/ Kitty’s Gone Milking/ King of the Clans

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat

Larry Kinsella

Irish harmonica player, 1937 recordings.

-

Greencastle/ Boys of Blue

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

The Blackbird

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

Donald Davidson:

Irish harmonica player, 1930 and 1931 recordings.

-

Sterling Castle/ Soldier’s Joy

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A -

Moneymusk/ Devil Among the Tailors

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat -

Highland Wedding

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

HJ Woodall:

English harmonica player, early 1920s recordings.

-

Irish Jigs & Reels

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G -

The Punjab March

- Key of F harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of F

PC Hopkinson:

Irish harmonica player.

-

Coisley Hill (March)

- Key of B flat harmonica minor (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of B flat minor. -

Irish Airs

- Key of F harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of F -

Scottish Airs

- Key of F harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of F -

Scottish Two Step

- Key of F harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of F

Mick Kinsella:

Irish harmonica player, 2012 recording, live at the Willie Clancy Week 9-23-12

-

Call & Response/ Mama Blues

- Key of B harmonica, played in the position in the key of F

John Murphy:

Irish harmonica player, 2012 recording, live at the Willie Clancy Week 9-23-12

-

Mason’s Apron

-

Key of C harmonica, played in the first position in the key of C.

-

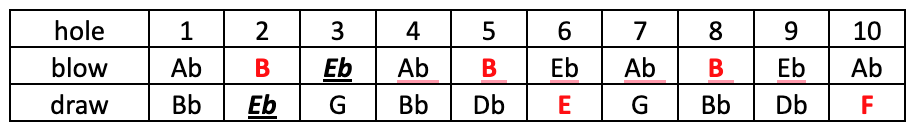

Here the holes 2 & 3 draw are tuned down two half steps lower than in the Standard harmonica tuning (retuned notes are in red):

Pip Murphy:

Irish harmonica player, 1990s recording.

-

The Congress/ The Heather Breeze/ The Earl’s Chair

-

Key of A harmonica. Played in the 2nd position for the first song, and in the 1st position for the second and third songs

WV Robinson:

-

English and Australian harmonica player, 1926 recordings.

-

Darkie Dances (including Turkey in the Straw)

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C -

The Regiment Passes By

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat

Brendan Power

- New Zealand/ Irish harmonica player

129. The Bucks of Oranmore

- key of D harmonica, in the Melody Maker Tuning, played in the 1st position in the key of D

Donald Black

– Scottish harmonica player

-

Slow Air/ Westwinds

- Slow Air is played on a key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

Westwinds is played on a key of A autovalve harmonica (double sets of reeds), in the 1st position in the key of A, and on a key of D autovalve harmonica in the 1st position in the key of D

131. Pipe Slow Air

- key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

Winslow Yerxa

– American/ Quebec harmonica player

-

Drops of Brandy/ Hay in the Loft Two Step

- Drops of Brandy is played on a key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G.

- Hay in the Loft Two Step is played on a key of Low D harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of D

-

La Vase du Peril

- played on a key of D harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of D

134. La femme d’un soldat

- played on a key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D.

Bruno Kowalczyk

– Quebec harmonica player

135. Reel Levis Beaulieu

- key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A.

136. Reel Quebecois

- key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G, and a key of C harmonica played in the 1st position in the key of C

137. Valse d’Orda

- key of C harmonic minor harmonica, (minor scale with the 3rd, and 6th notes flattened one half step), played in the 1st position in the key of C minor

Sonny Boy Williamson::

- American harmonica player, l963 live recording

-

Bye Bye Bird

-

Key of Low D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A.

Sonny Terry:

- American harmonica player, late 1940s and early 1950s recordings.

-

Rain Crow Bill (with Woody Guthrie commentary):

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Harmonica and Washboard Breakdown (with washboard accompaniment):

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Fox Chase

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Lost John

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A

-

Train Whistle Blues

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the keys of F and B flat

-

New Love Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Harmonica Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

Eddie Hazelton:

- American harmonica player, early 1970s recordings.

-

Mocking the Train/ Mocking the Dogs

- Key of B harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the key of F# & B

-

Poor Boy Travelling From Town to Town

- Key of B harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F#

-

Hard Rock is My Pillow

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Motherless Children Have a Hard Time

- Key of B harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F#

-

Throw a Poor Dog a Bone

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Red River Blues (Crow Jane)

- Key of harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

Peg Leg Sam:

-

South Carolina harmonica player, mig 1960s and early 1970s recordings.

-

John Henry (live 1973)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

John Henry (live 1965)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the position in the key of D

-

John Henry (live 1972)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

John Henry (album)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Lost John (live 1965)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

-

Lost John (album)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Greasy Greens (album)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Greasy Greens (live 1973)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Greasy Greens (live 1972)

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G

Dr. Ross:

-

Chicago harmonica playrt, early 1970s recordings.

-

Mama Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Good Morning Little Schoolgirl

- Key of E harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of B

-

Fox Chase

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

Artelius Mistric:

-

Cajun harmonica player, 1929 recordings.

-

Belle of Point Clare

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

-

Tu Ma Partient (Yo Belong to Me)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

Isom Fontenot:

- Cajun harmonica player, 1960s and 1970s recordings.

166. La Betaille [Dans Le ‘Tit Arbre] (The Beast)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D. –(when Rick Epping plays this piece he bases it more in the 3rd position, in the key of A minor).

167. La betaille dans letit arbre (The Beast)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

168. Contredanse Francaise

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

169. You Had Some But You Don’t Anymore

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

170. Two-Step De Lanse Maigre

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G (this track is a little flat)

171. N’one ‘Dam Et Tante Bassette

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

172. Madelaine

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st & 2nd positions in the keys of G & D

173 . La Valse De Misere

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

174. Crowley Two-Step

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

175. La Betaille [Dans Le ‘Tit Arbre] (The Beast)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

176. Waltz

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

177. Two Step

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

178. Contradance for Kids and Grandkids

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

179. Dance of the Mardi Gras

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

180. Two Step

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

181. Gay Dance

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

182. La Calligue Two Step

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

183. Julie Blonda

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

184. Waltz

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

185. Cajun Breakdown

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of G

186. La Betaille [Dans Le ‘Tit Arbre] (The Beast)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

187. La Betaille [Dans Le ‘Tit Arbre] (The Beast)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

Taj Mahal:

- American musician – early 1970s recordings.

188. Cajun Tune

- Key of harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of B flat

189. Sounder Chase a Coon

- Key of A harmonica, played in the position in the key of A

Doc Watson:

-

North Carolona Old Time musician, recordings from the 1960s forward,

-

Rain Crow Bill

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A

Doc learned this from Henry Whittier.

-

Mama Blues

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G

Doc learned this from William McCoy.

-

Cripple Creek

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Sally Goodin/ Cripple Creek

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat for Sally Goodin’; and played in the 2nd position in the key of F for Cripple Creek

-

Home Sweet Home

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C

Lonnie Glosson:

-

Arkansas harmonica player, recordings from the 1940s forward,

-

I Want My Mama (from Starday EP)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the position in the key of E

-

I Want My Mama

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of B flat

-

I Want My Momma (live at the Kerrville Folk Festival)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Talking Harmonica

- Keys of A & D harmonicas, played in the 2nd position in the keys of E and then A

-

Fast Passanger Train

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Panama Limited

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

-

The Fast Train - Ozark Cat Chase --(“car” ? chase--but probably “cat” chase) ?

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

-

Cat Chase Fight

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

-

Lonnie’s Fox Chase (1936)

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

-

The Fox Chase

- Key of A harmonica, played in the position in the key of E

John Sebastian:

- New York musician, recordingd from the early 1970s forward.

-

Blues for Dad/ JB’s Happy Harmonica (on live album)

- Key of E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of B flat for Blues for Dad; and played in the first position in the key of E flat for JB’s Happy Harmonica

-

Blues for Dad/ JB’s Happy Harmonica (live)

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key F of for Blues for Dad; and played in the first position in the key of B flat for JB’s Happy Harmonica

-

Blues for Dad/ JB’s Happy Harmonica (live at the Nofo Festival)

- Key of F harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key C of for Blues for Dad; and played in the first position in the key of for JB’s Happy Harmonica

-

Blues for Dad/ JB’s Happy Harmonica (live)

- Key of E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key B flat of for Blues for Dad; and played in the first position in the key E flat of for JB’s Happy Harmonica

-

Blues for Dad (live on Prairie Home Companion)

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G

Raymond Chance Simmons:

- American harmonica player, 1974 recordings.

- I met Raymond in 1974 when I picked him up hitchhiking in Los Angeles. He saw my harmonica on the dashboard and asked if he could play it. He played these songs and I asked him how he got the second sound on the harmonica and he showed me the tonguing method, of putting the tongue on the holes of the harmonica, blocking off some notes, and then lifting the tongue to get chords sounding along with the melody. A couple of days later recorded him playing these three songs. Also, he played the harmonica backwards.

210. Harmonica and Spoons Breakdown

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F

He held the harmonica in his left hand and played the percussion instrument that he devised with his right hand – it was two spoons tied close together, with finger cymbal attached to the end of the spoons.

211. B Flat to F Splashes

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd and 1st positions in the keys of F and B flat

212. F7th Breakdown

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F

Hidero Sato

-

Japanese harmonica player, 1980s recordings.

213. Kojo No Tsuki

- Key of A harmonic minor harmonica (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of A minor

214. Haru O Utau

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

215. Sukara No Waltz

- Key of A flat harmonic minor harmonica, (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of A flat minor

216. Yoimachigusa

- Key of G harmonic minor harmonica (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of G minor

217. Yashi No Mi

- Key of A flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A flat

218. Kazoe Uta Hensokyoku

- Key of A flat harmonic minor harmonica (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of A flat minor

219. Ituske No Komoriuta

- Key of A harmonic minor harmonica (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of A minor

220. Hakona No Uta|

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

221. Kisha No Tabi

- Key of Low F# harmonica, played in 1st the position in the key of F#

222. Aketombo

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

223. Hakone No Yama No Yosete

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

Howard Levy (live solo recordings):

-

American harmonica player, 2000s recordings.

224. Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring (live 2018)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A

225. Amazing Grace (live at SPAH 2010)

- Key of low E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st & 12th positions & the 2nd position again, in the keys of B flat, E flat, A flat, and B flat respectively

226. Amazing Grace (live in London 2007)

- Key of low E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st & 12th positions & the 2nd position again & the 1st position again & the 12th position again, in the keys of B flat, E flat, A flat, B flat, A flat, E flat, and B flat, and the 2nd position again respectively

227. Amazing Grace (live at JAM Inc)

- Key of low E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st & 12th positions & the 2nd position again, in the keys of B flat, E flat, A flat, and B flat respectively

228. Amazing Grace (live at Bass at Beach 2006)

- Key of low E flat harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st & 12th positions & the 2nd position again, in the keys of B flat, E flat, A flat, and B flat respectively

229. This Land is Your Land

- Key of low E flat harmonica, played in the 12th & 6th &12th & 1st & the main part of the song in the 12th position, in the keys of A flat, F minor, A flat, E flat, and for the main part of the song in the keys of A flat and E flat.

Will Scarlett:

-

California harmonica player, early 1970s recording.

230. Third Position Dorian Blues (at Lou Curtiss harmonica workshop)

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 3rd position in the key of D minor (this track is flat and sounds in the key of C# minor).

Will Scarlett can also be heard playing in the 3rd position (in the keys of A Major and A minor on a G harmonica), with early Hot Tuna, on the songs Come Back Baby, Uncle Sam Blues, and Know You Rider (he played everything on a G harmonica (in the keys of G Major, D Major, A Major, and A minor) with them on their first two albums from 1969, HOT TUNA, and LIVE AT THE NEW ORLEANS HOUSE – BERKELEY, CA – 1969).

Theodore Bikel:

American musician, 1956 recording.

231. Harmonicas (Improvisation & Russian Type Melody

- Key of E harmonic minor harmonica (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 6th notes, and with the Major 7th note), played in the 1st position in the key of E minor; for the second melody he also briefly plays a key of G Major harmonica for the quick modulation to the key of G.

Mel Lyman:

-

American harmonica player, 1965 recording.

232: Rock of Ages

- Key of C harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of C Played at the very end of the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

Marty Gardner:

American harmonica player

-

Freight Train & Model T Ford

- Key of D harmonica, played in the 2nd & 1st positions in the key of G & D

-

Mama Blues

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

Mike Stevens:

- American harmonica player, 1990s recording,

235. Jesse’s Request

- Key of C minor Aeolian mode (aka C Natural minor) harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of G minor

Mark Graham:

- American harmonica player, 1991 recordings,

236. Hook and Mouth (live 1991)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the position in the key of E

237. Blues with 3rds (live 1991)

- Key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E

Jason Ricci:

- American harmonica player, 2000s recordings.

238. Improvised Solo Piece (live 2008 in Fort Lauderdale)

- Key of B flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of F

239. Jason Solo (live)

- Key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D

240. Fox Chase/ The Altitude in Colorado Sucks (live at SPAH 2015)

- Key of A flat harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E flat

Richard Hunter:

- American harmonica player, 1990s and 2000s recordings.

- Many thanks to Richard Hunter for the help with this information

241. Blues for Charlie

- key of B flat Dorian harmonica, played in the 5th position in the key of G Natural minor with a Diminished 5th note, here the Db note.

Note: This tuning is named for the Dorian mode (minor scale with flatted 3rd & 7th notes), in the 2nd position

.png)

242. Hymn for Crow

- key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of E (also this piece could be played without any change on a key of A Country tuned harmonica.

- Country Tuning is the Standard Richter with the draw 5 reed raised 1/2 step. The reason it's interchangeable with Standard tuning for this piece is that the 7th degree of the scale (hole # 5 draw) is not used.

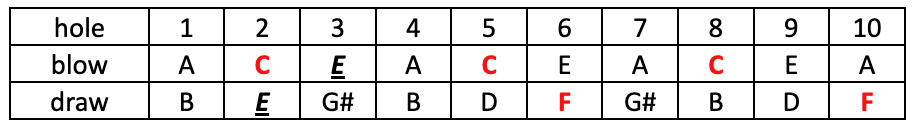

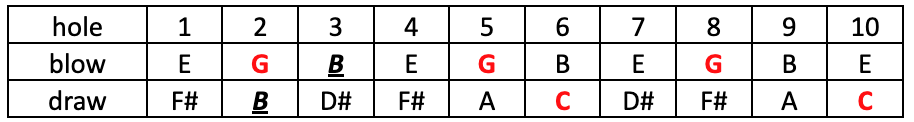

Key of A harmonica Country Tuning

243. Widow’s Walk

- key of A flat Natural minor harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of A flat minor. The Natural minor harmonica is named for the key in that is in the 2nd position, here A flat minor (the 1st position is a 4th interval higher, the key of D flat minor.

- and this is the same tuning if you are calling the key G# minor:

244. Winter Sun at Nobska

- key of E flat harmonica, played in the 3rd position in the key of F minor.

245. Rock Heart

- key of F Natural minor harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of B flat minor.

- The Natural minor harmonica is named for the 2nd position (which would be B flat minor), and the 1st position, as played here, is a 4th interval higher, for the key of F minor.

246. Golden Mel

- key of E flat harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of E flat.

247. From Above

- key of A harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of A.

248. Requiem

- key of G harmonica, played in the 2nd position in the key of D.

249. New Country Stomp

- key of A Melody Maker harmonica, played in the 1st position in the key of D, and in the 2nd position in the key of A

- the Melody Maker harmonica is named for the 2nd position, here the key of A

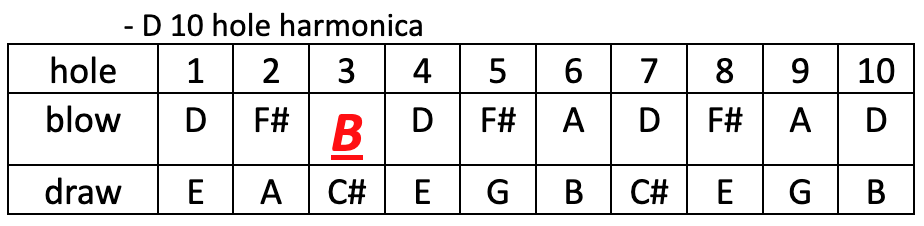

- D 10 hole harmonica

Peter “Madcat” Ruth

- American Harmonica player - 1990s or 2000s recordings

250. N’tah

- key of harmonica, played in the position in the key of

251. Steam Train (Steam Train and Rock Island Line)

- key of harmonica, played in the position in the key of

252. Steam Train (Harmonica Crazy)

- key of harmonica, played in the position in the key of

The Hawaiian Slack Key Blues style basically is playing deeply, profoundly, and simply, staying with the melody and a few ornaments, usually in a slow tempo, most evident in the older playing styles, such as that of the late Auntie Alice Namakelua (1892-1987).

This also applies to the Hawaiian deep Blues style, where songs are played with a slow deep swing, and sometimes with a strong accent on beats two and four of the measure. It could be described as a way of playing, as well as the essence of the songs themselves. The Hawaiian Slack Key Blues style has been used prominently by Leonard Kwan (1931-2000), Sonny Chillingworth (1932-1994), Ray Kane (1925-2008) Led Ka’apana, George Kuo, Dennis Kamakahi (1953-2014), Keola Beamer, Bla Pahinui, Moses Kahumoku (1953-2019), George Kahumoku, Jr., and George Kahumoku, Sr.

Some of these Hawaiian Blues songs are: Moana Chimes, Muli Wai, Punalu`u, E Hulihuli Ho`i Mai, Mi Nei, Radio Hula, Kalama Ula, Ka`ena, Meleana E, Kukuna O Ka La, Pua Be Still, Ho’okena (when played slowly), Na Pua Lei ‘Ilima, Kauhale O Kamapua`a, Dennis Kamakahi’s Nani Ko`olau, Keiki Mahine, Kalena Kai, My Yellow Ginger Lei (Lei Awapuhi), Maile Lau Li`i Li`i, Aloha Ku’u Home Kane’ohe (aka Kane’ohe) , E Mama E, Ua Like No A Like, Lepe Ula Ula, Aloha Chant, Wai Ulu, Noe Noe, Sanoe, Queen’s Jubilee (this is the same melody as ‘Ike Ia Ladana), Ke Aloha, E Lili’u E , Inikiniki Maile (Gentle Pinches of the Wind), Lihue, Papakolea, Pua Sadinia, Ka Lei E, Na Hoa He’e Nalu, ‘Akaka Falls, Hilo Hanakahi, Manuela Boy, Ka Manu, None Hula, Pua Makhala, Matsonia, Nana’o Pili, and the ultimate Hawaiian blues song, Kaulana Na Pua, written by Ellen Prendergast in 1893 after the overthrow of Queen Lili`uokalani and the annexation of Hawai’i by the United States, and Ku`u Pua I Paokalani , written by Queen Lili`uokalani when she was under house arrest after the overthrow. Other Hawaiian songs can be played this way as well.

SECTION I:

- I: Brief History of Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar (Ki Ho`alu)

- Ia: Technical Essay on Slack Key Sub-Traditions

SECTION II:

SECTION III:

SECTION IV:

SECTION V:

SECTION VI:

SECTION VII:

SECTION VIII:

George, along with Jay Junker, has written the liner notes for the Hawaiian Slack Key guitar album releases. Go to www.dancingcat.com, then to “Artists”, then the liner notes are with each album that is opened.

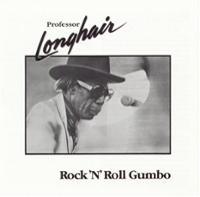

Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd 1918-1980) was the founder o f the New Orleans R&B piano scene in the late 1940s. Some of his influences were the great blues and Boogie Woogie pianists of the 1920s and the 1930s, especially Meade Lux Lewis (1905-1964), Pine Top Smith (1904-1929), and Jimmy Yancey (1898-1951). Also Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, and Little Brother Montgomery, as well as blues pianists in New Orleans, such as Archibald, Sullman Rock, Kid Stormy Weather, Robert Bertrand, and the great blues and jazz pianist Isidore 'Tuts' Washington (1907-1984); as well as New Orleans music in general, and the Caribbean and Latin music traditions. He was the reason I began playing again in 1979 after I had quit in 1977, when I heard his album with his first recordings from 1949 and 1953, NEW ORLEANS PIANO (Atlantic 7225), and especially his beautiful track from 1949, Hey Now Baby. Called "Fess", and beloved and inspirational to all who heard him, and the foundation of it all to me and many others, he had many inventions (as they were called by the great New Orleans pianist and composer Allen Toussaint) on the piano. He always put his own deep, definitive, unique and innovative way of playing on every song he composed or arranged. His playing, and his whole approach speaks volumes. New Orleans R&B piano starts here.

f the New Orleans R&B piano scene in the late 1940s. Some of his influences were the great blues and Boogie Woogie pianists of the 1920s and the 1930s, especially Meade Lux Lewis (1905-1964), Pine Top Smith (1904-1929), and Jimmy Yancey (1898-1951). Also Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, and Little Brother Montgomery, as well as blues pianists in New Orleans, such as Archibald, Sullman Rock, Kid Stormy Weather, Robert Bertrand, and the great blues and jazz pianist Isidore 'Tuts' Washington (1907-1984); as well as New Orleans music in general, and the Caribbean and Latin music traditions. He was the reason I began playing again in 1979 after I had quit in 1977, when I heard his album with his first recordings from 1949 and 1953, NEW ORLEANS PIANO (Atlantic 7225), and especially his beautiful track from 1949, Hey Now Baby. Called "Fess", and beloved and inspirational to all who heard him, and the foundation of it all to me and many others, he had many inventions (as they were called by the great New Orleans pianist and composer Allen Toussaint) on the piano. He always put his own deep, definitive, unique and innovative way of playing on every song he composed or arranged. His playing, and his whole approach speaks volumes. New Orleans R&B piano starts here.

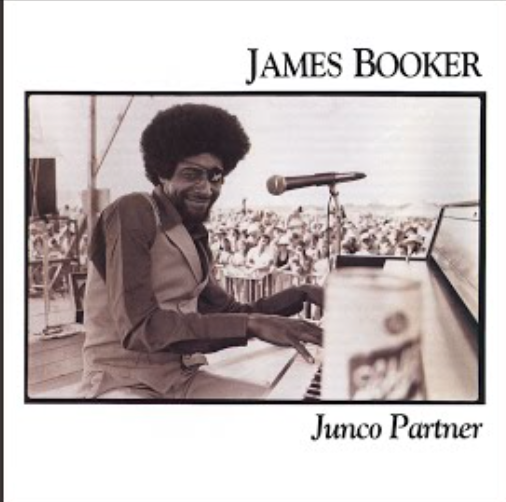

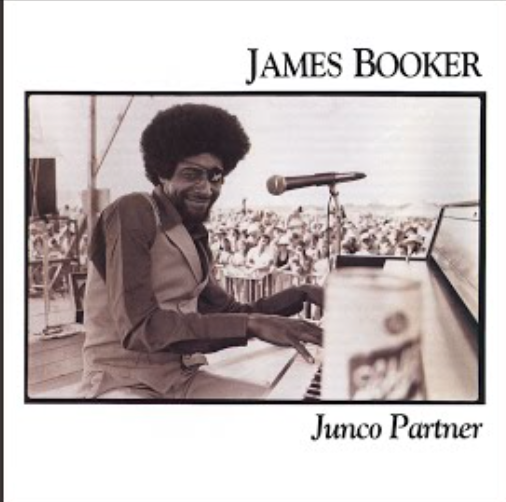

Professor Longhair inspired and influenced many pianists, including the late Dr. John (Mac Rebennack), the late Henry Butler, the late Allen Toussaint, the late James Booker, the late Fats Domino, Jon Cleary, Huey 'Piano' Smith, Art Neville, the late Ronnie Barron, Harry Connick, Jr., Tom McDermott, Amasa Miller, Josh Paxton, Davell Crawford, David Torkanowsky, Joe Krown, Tom Worrell, the late Cynthia Chen, and many many others.

New Orleans has a wonderful and incredible R&B piano tradition, beginning with the late Professor Longhair's recordings in 1949, and continuing today. Some of the great New Orleans R&B pianists playing there today are Jon Cleary, Art Neville, Davell Crawford, Joe Krown, Josh Paxton, Tom McDermott, Amasa Miller, David Torkanowsky, Tom Worrell, and many others. For listing of live performances and information on New Orleans music in general, see OFFBEAT MAGAZINE.

Fess had many inventions on the piano, as they were called by the great New Orleans pianist and composer Allen Toussaint (Allen talks about the influence this this video)

He always put his own wonderful fun-loving, yet deep stamp and twists on every song he played, whether it was an original composition or a great and often very different interpretation of another composer's song (hear his version of Hank Snow's I'm Movin' On, on Fess' album LIVE ON THE QUEEN MARY, and compare it to the original Hank Snow version). I always have open ears to notice these wonderful things when they happen in every song, and I notice more things every time I hear his recordings. He was so wonderful at telling stories with his instrumental solos, just listen to his instrumental Willie Fugala's Blues from his album CRAWFISH FIESTA; and with his lyrics as well.

At least 16 of Fess' inventions are:

- Fess' "Rhumboogie" (or sometimes called "Rhumba-Boogie") syncopated left and right hand playing style - see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO and ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT and BIG EASY STRUT:THE ESSENTIAL PROFESSOR LONGHAIR; and the song Her Mind is Gone from the albums CRAWFISH FIESTA and BIG CHIEF and BALL THE WALL! LIVE AT TIPITINA'S 1978 and BYRD LIVES!

- Another aspect of his "Rhumboogie" (or Rhumba-Boogie) left hand, using the Latin clave beat, with notes played on beats one, "two and", and four - he used this on many songs, as this was his favorite left hand bass to play - for example, see the song Junco Partner on the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO; and the song Hey Little Girl from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO (interestingly enough, this same clave beat was the favorite solo guitar bass pattern of the late Hawaiian Slack Key guitarist Sonny Chillingworth [1930-1994], who was very revered and influential in Hawai'i, similar to how Fess was in New Orleans).

- Push beats, with notes played just before the beat in left hand notes - sometimes for one note, and sometimes throughout a whole phrase - especially see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO and ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the song Walk Your Blues Away from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO; and the song Tipitina from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO.

- Rapid right hand triplets and sixteenth notes in many pieces - see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO and ROCK & ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the song Her Mind is Gone from the albums CRAWFISH FIESTA and BIG CHIEF; and especially in the song Hey Little Girl from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO.

- Double note crossovers rolls in the right hand, playing two notes together, one of them with the thumb and then slurring notes down, crossing the fingers over the thumb - especially see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO, and ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO, and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT, and also especially the piano solo in the song Hey Little Girl from the NEW ORLEANS PIANO album.

- Playing a right hand roll going up, then crossing the index finger down over the thumb at the end of the roll - on the song Bald Head, on the CRAWFISH FIESTA album, and his first version of Bald Head, from 1949 on both of his albums 1949, and also ALL HIS &78s, and also TIPITINA-COMPLETE 1949-1957 NEW ORLEANS RECORDINGS.

- Two hand rolls - see the introduction of the song Ball the Wall, from the album NEW ORLEANS PIANO, with the unique two hand roll with single notes in the left hand and chords in the right hand, followed by octave rolls in the right hand with single notes in the left hand, with the hands crossing sometimes; and the same rolls on the song 501 Boogie on the album HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972; and on another version of the same song, with the title Boogie Woogie on the album THE LAST MARDI GRAS (and this same track with the title 501 Boogie (with part of the introduction edited off) is on the album RUM AND COKE); and on the introduction and in the middle of another version of that song with the title Ball the Wall (aka 510 Boogie), on the album BALL THE WALL! LIVE AT TIPITINA'S 1978; and there is a similar roll in his instrumental piano break in the song It's My Fault on the album CRAWFISH FIESTA and also on the album BYRD LIVES;

- Two hand rolls ending with rapid right hand broken octaves with the thumb and then the little finger in the right hand - see the introduction for the song Tipitina, and also in the last verse of that song on the album ROCK & ROLL GUMBO; and the song Willie Fugal's Blues on the CRAWFISH FIESTA album, and on this song he used ascending rapid broken octaves going up in the right hand preceding them with a rapid lower left hand note in the fourth chorus of that song. He also sometimes used descending rapid broken octaves in the right hand preceding them with a rapid lower left hand note. And he also used descending broken octaves with the right hand alternating the broken octaves between using the thumb and then then the little finger, and then using the little finger and then the thumb in the songs in #5 just above. A related technique is the right hand broken octaves at the end of the song Mess Around on the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT.

- The incredible two hand drum roll technique in his instrumental break on the song Every Day I Have the Blues on the album LIVE ON THE QUEEN MARY (One Way Records S21 56844), and also on the albums THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT and BYRD LIVES!; and on the song Gone So Long, near the end of the song, on the album BYRD LIVES!.

- His wonderful and distinctive piano phrases for the chord progression of the late Earl King's (1934-2003) song Big Chief. His first version of these phrases was on his 1964 recording of Big Chief, reissued on the compilation album with Professor Longhair and other artists titled COLLECTOR'S CHOICE-FEATURING PROFESSOR LONGHAIR (Rounder Records), and it was also reissued on the compilation album with various artists MARDI GRAS IN NEW ORLEANS (on Mardi Gras Records). He later varied some of these piano phrases for Big Chief, which can be heard on the albums THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT and CRAWFISH FIESTA. It is amazing how he came up with this one (and all the others). What Fess said in the newly issued long in-debth interview with the late filmmaker Stevenson Palfi in the documentary FESSUP, about how he came up with things was that "I dream on it."

- His distinctive phrase for the IV chord (the C chord in the key of G, and the F chord in the key of C) - see the song Mean Ol' World from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO; and in his instrumental break in the song It's My Fault from the album CRAWFISH FIESTA; and in the song Gone So Long from the albums HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972 and MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE; and in the song Hey Now Baby from the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT.

- His use of repeating the tonic chord (the I chord) and/ or a tonic chord phrase in the right hand, over the IV chord (for example, in the key of C, playing the C Major chord over the F chord bass, creating the tonality of an F Major 7/9 chord) - see the song Hey Now Baby from the albums NEW ORLEANS PIANO, and ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the songs How Long Has That Train Been Gone and Stag-O-Lee, from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO - these latter two songs are in the key of F, so here for the IV chord, he played the F Major chord over the B Flat chord bass, creating the tonality of a B Flat Major 7/9 chord. Fess also sometimes played a roll with the tonic Major chord throughout the whole chorus - “ see the song Doin' It on the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and the song Gone So Long on the album HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972 and MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE.

- His temporary altering of the rhythm within a song - see the song Mean Ol' World from the album ROCK & ROLL GUMBO; and the song Everyday I Have the Blues from the album THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT; and the song Gone So Long from the albums HOUSE PARTY NEW ORLEANS STYLE - THE LOST SESSIONS 1971-1972 and MARDI GRAS IN BATON ROUGE.

- His playing of the root note of the chord on the beat "one-and" hesitating the bass note a bit, instead of playing it on beat one, in the second intro instrumental piano verse in the song Hey Now Baby, from the albums ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO and THE COMPLETE LONDON CONCERT, and in the instrumental piano solo in the song How Long Has That Train Been Gone from the album ROCK 'N' ROLL GUMBO.